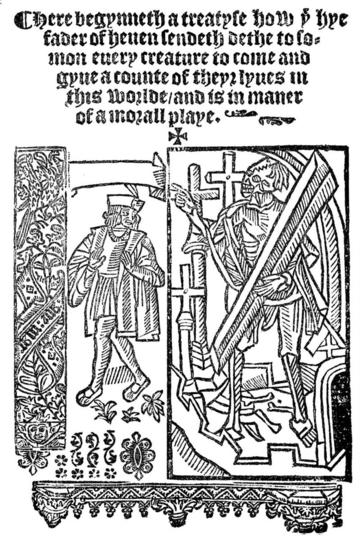

Covid-19 and the Religious Ethics of the Anthropocene: Can a 16th Century Morality Play Still Teach Us Anything?

When the covid-19 ‘lockdown’ measures came in, I was reading Everyman, a 16th century play.

I was reading it to prepare for a series of talks at the Ashmolean Museum as part of the TalkingEmotions project – a series which is postponed for now as we work out how to deliver them in our very new situation (a process of adjustment familiar to us all at the moment).

My talks were/are to be on the theme of pilgrimage – using some late Medieval pilgrimage badges depicting the ‘unofficial saint’ John Schorn (or Schorne) – a 13th/14th century clergyman who was reputed to have cast the Devil into a rather large leather boot! Badges were acquired by pilgrims as they visited holy sites, in this case those associated with Schorne.

I was re-reading the play Everyman as part of preparing for the talks, because it was produced around the same time as the Ashmolean badges.

Everyman is a ‘morality play’ – one of a number from this era intended (like a Medieval BBC) not just to entertain, but to educate – instilling their audience with what were regarded as fundamental moral and religious values.

In Everyman, the character ‘Everyman’ (a character who stands for, well, every man or human being), must learn to take the ‘pilgrimage of life’ seriously – a lesson he learns when he is visited by another character: ‘Death’.

As a result of the postponed talks, reading Everyman ceased to have its original purpose. Instead, it became a surprising resource for environmental humanities – reading it while entering lockdown revealed parallels between this 16th century morality play and the otherwise secular reactions to the covid-19 pandemic I was (and am) reading in the news.

Hope and ‘Good Dedes’

One (perhaps surprising) reaction to the current pandemic has been hope.

The hopes expressed vary, but a common one is that we will start to take climate change seriously. Human beings will realise that we are negatively affecting nature, and in doing so also bringing harm upon ourselves.

The realisation that we are vulnerable to nature, in the same way that nature is vulnerable to us, is frequently couched in the following terms: covid-19 is universal in scope and the great ‘leveller’ – it is harming and has the potential to harm everyone.

Of course, to hope awareness of human fragility will lead to seriousness about climate change, often includes the hope that human beings will act in response, and that that action will be effective.

Some have expressed this hope as grounded in a new-found belief in the power of the individual.

It’s been reported that some academics and journalists have changed their perspective. Dramatic and effective action against climate change is not only possible at an international and institutional level. Concerted individual action may also be a way of altering the course of climate change – in the same way that individuals have not only dramatically altered their behaviour in response to the covid-19 crisis, but, in doing so, become part of how that crisis (hopefully) will be abated.

Putting together the two points above – human vulnerability and the power of the individual – highlights parallels with Everyman.

Here, human fragility is represented by Death – and it is the realisation that death comes to every human being which awakens Everyman from his moral torpor.

In the play, Death tells Everyman that he must come with him on a ‘iourney’ (journey) that ends in ‘rekenynge’ (reckoning) before God. As a result, Everyman goes one by one to the characters, ‘Goodes’ (wordly possessions), ‘Felawshyp’ (friends), ‘Kynrede’ and ‘Cosyn’ (family), and asks them to come on Death’s ‘pylgrymage’ (pilgrimage) with him. Each refuse, and so Everyman fears that he must face Death’s journey and God’s reckoning alone. That is, until he learns that the one thing he had neglected – his ‘Good Dedes [deeds]’ – will stay with him at the end.

Everyman points to the relationship between 2 of the 3 theological virtues: hope and charity (or love). Everyman had placed his hope in the wrong things – wealth and fair-weather friends. He now has a different hope. Escaping Death and God’s reckoning is impossible – but he can place his hope in a life beyond death in friendship with God – a hope that expresses itself in ‘good dedes’ and ‘charyte’, in imitation of what Christian believe God to be: love.

Secular discussion does not place its hope in a life beyond death with God – but some of these naturalised accounts have described avoiding the climate crisis and overcoming covid-19 as a form of ‘salvation’: a salvation from the ‘reckoning’ of Nature itself. And, this hoped for salvation is consistent with key themes in Everyman.

Human beings must realise that we ‘belong to the material world’. Nothing is going to prevent us from dying as individuals. But this does not mean that individual life and individual action have no purpose or significance towards a higher goal: in this case, the continuance of human society, if not our survival as a species. On the contrary, the realisation that human beings are simply ‘natural life’, and that all natural life is precious – fragile and vulnerable – will, it is hoped, instil us with a greater love and respect for it – and so a newfound emphasis upon ‘charyte’ and ‘good dedes’ rather than short-term pleasure-seeking and consumption which leads to the abuse of nature and ourselves.

Faith and the Anthropocene

Of course, hope and charity are only 2 of the 3 theological virtues – the third is faith.

Faith in Everyman helps to frame some responses to covid-19 and climate change in the Anthropocene age.

The concept of the Anthropocene is part of recognising there is not some ‘raw’ nature out there left untouched by human beings – in the same way that there is not a piece of nature left untouched by the Sun – we are a climactic force of our own, and, in this new age of the Anthropocene, the dominant one.

Humanities scholars and commentators have located various tensions in the rhetoric surrounding the Anthropocene. Is it about recognising that ‘human’ has lost ‘equilibrium’ with ‘nature’; or is it a further sign of human ‘arrogance’ and ‘self-mythologisation’, where ‘nature’ is still something that can be ‘mastered’ by ‘human’?

The pertinence of the question is revealed by the fact that, even where there is agreement we are in the Anthropocene, within which human-made climate change is a central threat, the human-nature relationship does not always appear in the same terms.

Try to remember (it’s difficult, I know!) before lockdown when Matt Hancock, the UK Health Secretary, claimed that human ingenuity would make it possible for us to fight climate change without flying less. Examples of such human ingenuity include carbon offsetting schemes, which was, before lockdown, high on the government’s agenda.

Compare Hancock’s emphasis on human ingenuity and carbon offsetting, with support for reforestation as a form of carbon capture which recognises the ‘power of nature to heal’.

Both views have hope that human beings can and will and address climate change – but their hope is grounded in a different faith.

Hancock has faith in human action – our ‘good deeds’ alone. Such a faith does not lead to a fundamental change in behaviour. We do not give up ‘bad deeds’ but continue in them with our ‘good’ as counterbalance. Such an attitude accepts that this age is anthropocenic, but continues to emphasise ‘human’ over ‘nature’ when thinking about responding to problems brought about by, and in, this age.

Support for reforestation from scientists and environmentalists usually stresses that it is not sufficient on its own. Nonetheless, the language of ‘letting nature heal itself’ through the ‘magic of trees’ does highlight how it is easy to reverse Hancock, and emphasise ‘nature’ over ‘human’. Something that can also be seen in the reactions to covid-19 where (most famously in remarks from Miley Cyrus, Sarah Ferguson, and Jameela Jamil) the pandemic becomes a warning, punishment, or ‘clap back’, from ‘Mother Nature’.

We might query how these remarks anthropomorphise Nature; think it is possible to remove ‘human’ from ‘nature’; and encourage human passivity: the best thing humans can do is nothing – it is as we retreat indoors that Nature has time to heal. Perversely, overemphasising human passivity can go the same way as an overemphasising human activity: if we just need to let Nature heal, can we go back to how we were once that’s happened, so long as we give Mother Nature a break occasionally?

Again, Everyman offer a comparison. Here, faith is called ‘Knowledge’ – Everyman knows that his ‘charyte’ and ‘good dedes’ will not earn him salvation – salvation is not just about moral behaviour, but such religious practices as penance, and, even then, it is always up to God who will be saved. However, Everyman also knows through faith that he can have no hope of salvation without ‘charyte’ and ‘good dedes’. He does not believe his own actions inevitably bring him salvation from God’s ‘rekenynge’; nor does he believe that individual action is pointless, because everything is up to God.

In other words, Everyman’s faith guards against both complacency and fatalism – two moral dangers we must also guard against as we struggle with two physical dangers: covid-19 and the climate crisis.