Divided Cities: Culture, Infrastructure and the Urban Future

‘Divided Cities: Culture, Infrastructure and the Urban Future’

A Workshop funded by the British Council US and TORCH

TORCH Seminar, 24th June 2017

The workshop, ‘Divided Cities: Culture, Infrastructure and the Urban Future’, which took place at TORCH on 24th June 2017 and was generously funded by TORCH and the British Council USA, set out to explore the interlocking themes of urban identity, top-down planning, environmental degradation and migration in twenty-first century cities. It began with the premise that urban cultures and infrastructures have come to embody wider global conflicts, inequalities and divisions, and most crucially sought to ask how different cultural forms might possibly allow us to imagine new and alternative urban futures. Furthermore, it sought to emphasise a US-UK comparative perspective, and so the discussions were loosely structured around comparative city-specific studies of New Orleans, US and Newcastle, UK, each of which have been marked by controversial infrastructural developments and failures of the state, whether it be in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, in the case of the former city, or the recent intensification of austerity policies in the latter.

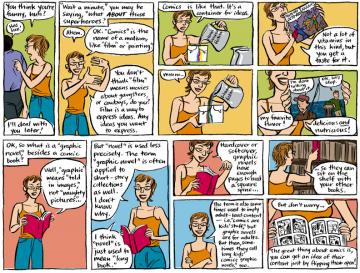

The day began with an opening keynote from comics artist and journalist Josh Neufeld, author of a number of comics including Titans of Finance (2001), A Few Perfect Hours(2004) and The Influencing Machine (2011). In his talk, however, Josh focused particularly on the genesis and journalistic and artistic processes leading to the creation of his documentary comic, A.D. New Orleans After the Deluge(2009), which follows the lives of several real-life New Orleans inhabitants before, during and in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina which struck the city in 2005. Speaking to the workshop’s geographical focus in this way, Josh first offered a lucid account of the disaster of Katrina itself, including the failure of the state to intervene effectively in the rescue, relief and support effort conducted in the weeks immediately following the hurricane, and the subsequent flooding that destroyed so much of the city’s infrastructure, and which had especially violent consequences for the city’s poorest inhabitants. He then pivoted to an account of the ways in which he collected his various witness testimonies and compiled these alongside other documentary evidence to draw the disaster from the perspective of a diverse set of individuals. The resulting comic, A.D., offers a careful slow journalistic attempt to correct the often racist coverage of this highly visual disaster as it circulated both at the time and in following years in the mainstream media.

Professor Hillary Chute offered a response to Josh’s talk, highlighting in particular the notion of ‘scale’ that is so integral to Neufeld’s work, as A.D. zooms in from planetary down to city-level in its opening panels. In so doing, it deftly foregrounds the natural disaster that was the hurricane itself, but also combines these with a critique of the manmade disaster that occurred at the level of the city’s infrastructure, not to mention the contrasting absence of state support infrastructure in Katrina’s aftermath. Chute, who’s own work, Disaster Drawn: Visual Witness, Comics, and Documentary Form (2016), explores why the comics form in particular is drawn to the documentation of witness testimony and humanitarian disaster, built on Neufeld’s talk to show how comics might offer an example of increasingly popular cultural forms that are able to represent the city—and the violence of the inequality contained in and perpetuated by its infrastructural layouts—so as to imagine alternative urban futures. Indeed, Neufeld also spoke about his follow up webcomic which returned to A.D.’s real life protagonists ten years after Katrina to find out how their stories had progressed, with some offering a promising story of recovery for New Orleans and its inhabitants, whilst others further indicating the continued failure of state infrastructure for the disaster’s victims.

After lunch, urban theorist, sociologist and director of the London School of Economic Cities Programme, Professor Suzanne Hall, gave the day’s second keynote lecture in which she offered an erudite summary of recent research undertaken into ‘migrant infrastructures’, particularly as they are oriented around key high streets in cities in the UK. Using astonishing visuals that showed the geographical origins of high street residents before mapping these against a world map, Hall emphasised the global networks that are contained and circulated at street level. Furthermore, she used birds-eye view diagrams of migrant shops to explicate the complex interactions and logics of migrant economies, showing how an understanding of the physical infrastructural space of the city is fundamental to comprehending the way in which they work. In so doing, Hall’s talk resonated with Neufeld’s similarly meticulous documentation of city space that he required for his visual reconstruction of the experience of Katrina victims—each project, in its different ways, used innovative forms of visualisation in order to bring the everyday and exceptional use of the city to life. The notion of scale was again crucial here, as the global city—its high streets, housing, businesses, and communities—operates simultaneously at huge planetary and specifically localised levels.

The following panel was comprised of three shorter talks from Mike Rubenstein of Stonybrook University in the US, and a previous contributor to the ‘Planned Violence’ Network’s final workshop back in October 2016; Hanna Bauman, from the architecture department at the University of Cambridge; and Dom Davies, the project facilitator of the ‘Planned Violence’ and ‘Divided Cities’ Networks. Rubenstein’s opening presentation thoughtfully mapped the flow of syntax as it jolts against the mechanical infrastructure of passages from James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922) onto the politics of water infrastructure in twentieth-century Ireland. From here, the paper brought the workshop firmly into the present with a reading of Mike McCormack’s recent winner of the Goldsmiths prize for fiction, Solar Bones (2016), the entirety of which is written as one long sentence. Building on the notions of formal and infrastructural flow, Rubenstein further linked these innovative narrative techniques to current debates around water as a publicly owned—or by contrast, and as is increasingly the case, highly marketable—resource and/or commodity.

Dom Davies then offered a brief account of the urban infrastructure of Newcastle-Upon-Tyne as it is depicted in Ken Loach’s recent social realist film, I, Daniel Blake (2016), situating its brutal depiction of the effects of austerity in the form of benefit cuts and sanctions in the North East within the historical context of Britain’s vote to leave the European Union in June 2016. Reading Newcastle’s flashy neoliberal skyline as a correlate of capitalist realism, Davies argued that Loach’s social realism undermined arguments for austerity policies—and a hyper-capitalist society more generally—through its form and the urban landscapes it depicts. He then traced the way in which the film became coupled with Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour movement, Momentum, which itself came to occupy online and urban spaces in the real world to leverage social change.

Finally, moving to the very different context of East Jerusalem in Palestine/Israel, Hanna Bauman explored the politics of the supply (or more often, withdrawal) of basic infrastructural services such as waste removal, as they are mobilised toward the expulsion of Palestinians from their lands. Nevertheless, and in keeping with the theme of the workshop, Bauman showed clips of Palestinian artist Khaled Jarrar’s films and other artistic projects that undermine Israel’s segregation of East Jerusalem from the rest of the West Bank. These included the drilling of a hole through the concrete segregation barrier, a huge wall built by the Israeli state and that has destroyed communities by weaving through the area, in order to pass Palestinian goods through from one side to the other—in another example, Jarrar filmed the miserable walk undertaken by Palestinians through Israeli sewers, again to undercut the barrier, so that they could visit holy sites in Jerusalem for a religious festival.

To bring the day to a close, authors Selma Dabbagh and Courttia Newland repositioned literary and creative writing back at the centre of the workshop’s discussions by reading from their work. Dabbagh began the session by reading excerpts from a forthcoming novel that offers accounts of the politics infusing the secluded microcosmic spaces of segregated communities and urban spaces scattered across the Gulf. Against a backdrop of contrasting seascapes and restrictive infrastructures, Dabbagh introduced the cast of flamboyant and provocative characters that will people her new novel, and about which we are very excited to learn more in coming months. Newland then read a powerful short story inspire by the death of Mark Duggan, but that charts the experience of a Black man’s fatal encounter with the Met police by moving backwards in time, beginning with the moment of the violent confrontation and tracing the protagonist’s movement right through to his gentle farewells with his mother as he leaves the relative safety of his house. Newland also then read from a new piece of dystopic fiction that imagines a large walled infrastructure encircling a futuristic London, a boundary that the story’s protagonist attempts to cross.

Both contributors to earlier workshops during the ‘Planned Violence’ Network, we were delighted to welcome these authors back to continue our exploration of themes of urban violence, and their readings stimulated much discussion over the wine reception and then at the workshop dinner. By bookending the academic papers with talks from cultural and literary practitioners, the workshop was able once again to emphasise the importance of these creative re-imaginings of city spaces as not only a diagonistic tool able to throw the violence of urban planning into relief (and of which the recent Grenfell Tower catastrophe, highlighted by Project Leader Elleke Boehmer in her opening comments, is a terribly tragic example). Furthermore, the workshop also emphasised throughout that cultural production about the city is often invested, even if only in small ways, with the capacity to imagine alternative, less violent and more inclusive urban futures.

Dominic Davies