Birth Throughout History - Virtual Exhibition

Tales of births - normal, abnormal, monstrous, fantastic – have always fascinated. Birth is the one experience all readers have shared, yet cannot remember for themselves; know only through other people's accounts of what happened. Birth is also the moment of entry to the world, yet not the first moment of existence. It is when – before the days of ultrasound scans or X-rays – others could finally set eyes upon what had existed, had lived, for many months before, in the mysterious, sealed world of the womb. By adopting a historical lens from the Renaissance to the present, we can gain fresh insights into some of the recurrent debates in women’s healthcare and fetal medicine.

I have explored this approach in my recent work, such as the chapter ‘Birthing tales and collective memory in recent French fiction.’ In Motherhood in Literature and Culture. Interdisciplinary Perspectives from Europe. Ed. G. Rye, V. Browne, A. Giorgio, E. Jeremiah, A. Lee Six (Abingdon-New York : Routledge, 2017), pp. 58-69, and the chapter I contributed to the catalogue accompanying the exhibition in 2019 at the Château de Blois on Birth and Childhood in the Renaissance (`Conjurer la mort`). In Enfants de la Renaissance. ed. Caroline zum Kolk, François Lafabrié, Château de Blois: In fine, 2019, pp. 30-37.

Valerie Worth-Stylianou sharing a discussion of some of the posters with midwifery students at Oxford Brookes University.

In this short post, we invite you to take a virtual tour around an earlier exhibition that took place at the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists in 2015. This ran for eighteen months, in the Learning and Teaching centre of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists in London. It was curated by Valerie Worth-Stylianou and her Knowledge Exchange partners, Janette Allotey (Chair of the De Partu research group on the history of childbirth) and Carly Randall (then archivist at the RCOG). The exhibition was a key part of the Knowledge Exchange project celebrating 500 years of changing perceptions about pregnancy, and featured materials from the College’s own archives, contextualising them and inviting the viewers to reflect on the constants and changes in pregnancy and childbirth. The historical images resonated with health professionals and general audience alike.

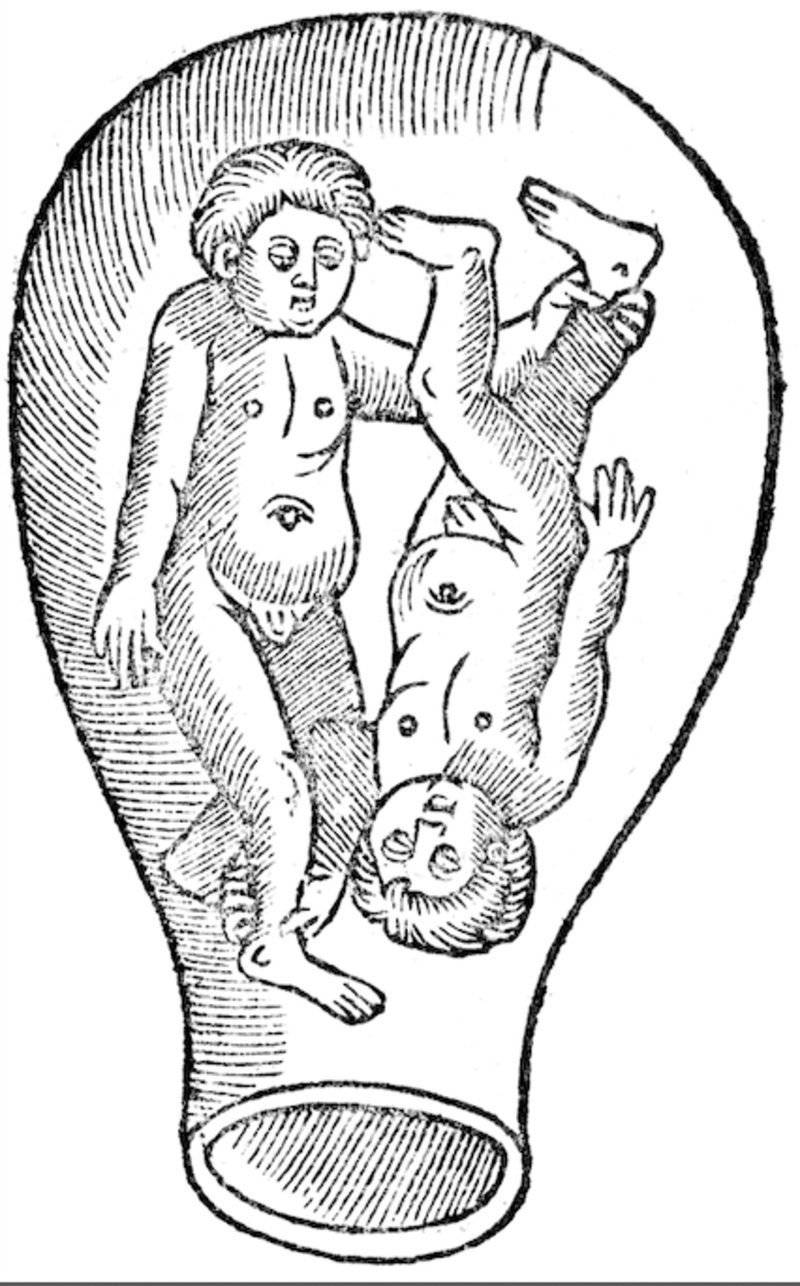

Imagining the fetus before X-ray and ultrasound.

Ultrasounds have become a standard procedure in almost all pregnancies in the developed world, and parents-to-be thus follow the development and growth of their baby. Yet before the twentieth century, images of fetuses were confined to obstetric textbooks, and in early printed books were often impressionistic, designed primarily to allow the student or practitioner to consider the position of a fetus for delivery. Hence, most images represented exceptional or abnormal positions, with breech positions, transverse lies and multiple pregnancies dominating.

Eucharius Rösslin, originally an apothecary and then physician in the German town of Worms, published a textbook, Der Swangern Frawen und Hebammen Rosengarten (A Rose Garden for Pregnant Women and Midwives) in German in 1513, which circulated widely over the next century, being translated into Latin and various European languages including in 1540, into English (The Byrth of Mankinde). Some 30 copies are held in the RCOG’s Library The plates in Rösslin’s work, including this one, were copied from a much-earlier work attributed to Muscio (probably composed c. 500, and preserved in a manuscript c. 900). There is no attempt to represent the placenta or umbilical cord; rather, the fetus is a miniature child – complete with a full head of hair – and, in the case of the upright twin, perhaps some malicious intent towards his brother...

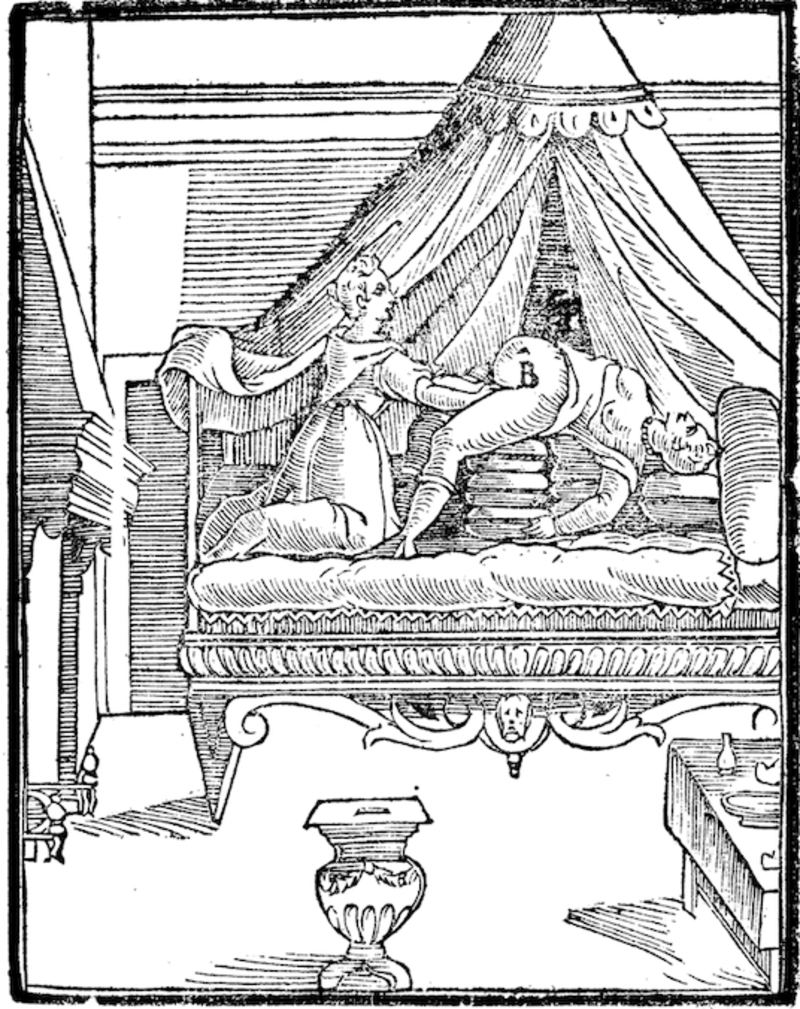

Midwife assists mother during a difficult delivery (1601)

Scipio Mercurio was originally a monk, but then trained as a surgeon, working in Italy in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. His book La Commare o riccoglitrice (The Midwife) appeared in Italian in 1601, and remained in print for over a century, also being translated into German. Here, the illustration shows the midwife supporting the mother through a difficult delivery. The midwife is kneeling on the bed, on the same level as the woman, and has piled cushions under the small of the woman’s back, to widen the pelvic outlet and realign the fetus.

Midwifery manuals of the early modern period encouraged the midwife to be resourceful in using any home comforts to hand (sheets, cushions, chairs) so that the woman adopted a comfortable position as labour progressed, and especially one that facilitated delivery. By the mid-seventeenth century, and the advent of the male-midwife surgeon, a supine position in bed became associated with a passive delivery; in contrast, the woman in this image has her back raised for a specific anatomical reason.

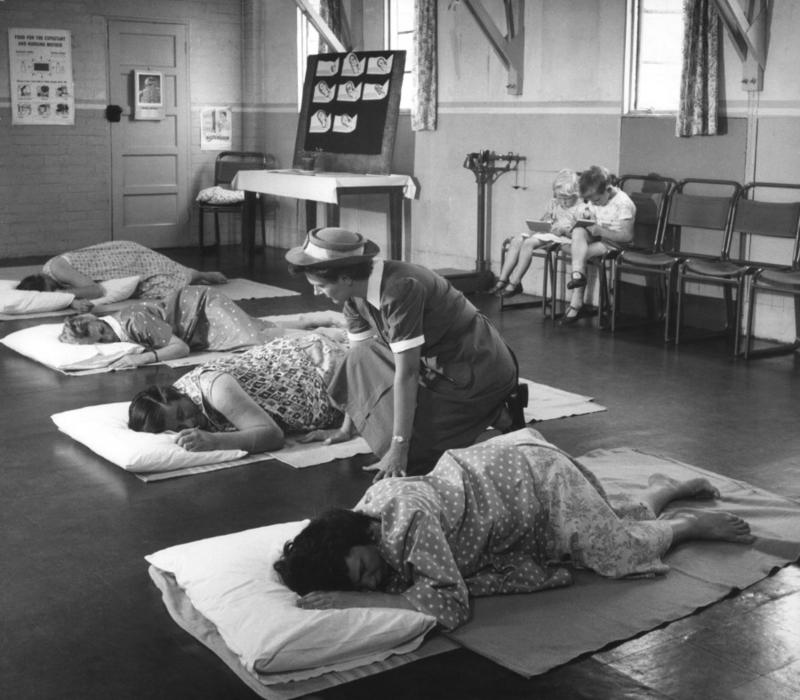

Domiciliary midwife’s class for pregnant mothers (c. 1950-60)

This photograph (RCM Archive : rcm/ ph7/2/2) depicts a midwife taking a relaxation class for expectant mothers, c.1950-1960. While it was possible for women to read pregnancy manuals, attendance at ‘Mothercraft’ classes, as they were then called, was encouraged. According to Margaret Myles (A Textbook for Midwives, 1956), women were advised on how to keep fit, maintain a good posture in pregnancy, eat well, rest, and on how to relax in pregnancy and in preparation for birth. Physiotherapists were available to advise on exercises to help ‘stretch the pelvic floor muscles and loosen the pelvic joints’.

A series of relaxation classes were usually held in a local health clinic or village hall for small groups of women. According to Myles, women were advised to wear loose clothing, with ‘corsets removed, shoes off, stockings rolled round the ankles; her bladder empty’. Pupil midwives were taught the principles of public speaking and the importance of impeccable personal presentation in creating a good impression of the profession. (Notice the domiciliary midwife’s felt hat!) Pupils were also trained to use teaching aids (a chart can be seen in the background of the photograph) and to perform practical demonstrations for the mothers; some of these teaching materials are available in the RCM’s archives.

The women in the picture are there without their partners – Myles suggested that evening classes for ‘husbands’ and wives should also be available, at which husbands could be seen alone, and the opportunity used to advise them of their responsibilities for ensuring amongst other things, that their ‘wives’ carried out the doctors’ instructions...

In the photograph, the children appear to be seen and not heard, sitting quietly on a chair, with a book. Their presence may have been an exception to the general rule.

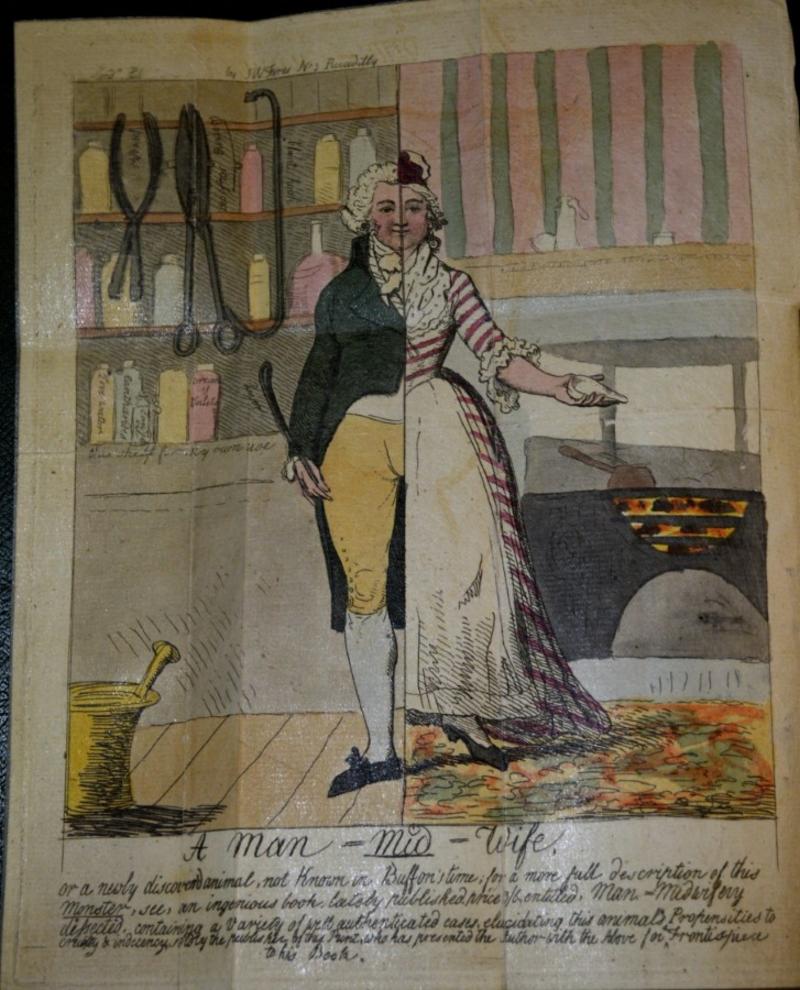

Man mid-wife or female midwife? (1795)

Folded into the front of a book published in London in 1793 (and republished in 1795) under the name of John Blunt – but in fact the work of Samuel Fores, a caricature publisher – was a very detailed illustration, bisected in the middle. It showed ‘a newly- discovered animal’, the man mid-wife. Man-midwifery Dissected rails against the fashionable popularity of what Fores considered a grossly indecent practice, namely allowing men to deliver women, and he warns husbands of the dire consequences of allowing such men into the bedrooms of their wives. Louise Bourgeois (see poster 1) had advanced very similar arguments – albeit without the comic illustration – in the early seventeenth century, when surgeons specialised in deliveries were just starting to gain ground in Paris. Resistance was also voiced in England by midwives such as Sarah Sharp, Sarah Stone and Elizabeth Nihell. Fores is probably suggesting that the citizens of London should defy what he held to be a ‘French’ practice.

The advent of male midwives brought a conflict of professional and economic interests, compounded by a sense of outrage at male practitioners touching the vagina of women patients. Indeed, early midwife surgeons used to operate with their hands and arms under sheets, so that they could not look at a woman’s genital region as they worked. In Fores’ caricature, there are simplistic and obvious contrasts: the clothing of the midwife is informal, not expensive, unlike the outfit of the surgeon. She heats water, relies on a comforting fire, and is probably using the pan on the stove to prepare some sustaining broth for the mother or ‘paps’ for the baby. The surgeon is depicted with supplies of expensive medicines (some of which are love potions or remedies for venereal disease!), and, above all, metal instruments. The right to use forceps has long been a major distinction between midwives and surgeons.

With thanks to Kristina Gedgaudaite for her valuable editorial help with this blog.

Valerie Worth-Stylianou received her MA and DPhil from Oxford University. She was a Lecturer at the Université Rennes 2 and then at King’s College London, before becoming Research Professor of French at Oxford Brookes University and then Professor and Head of Modern Languages at Exeter University. In 2009, she took up her current post as Senior Tutor of Trinity College Oxford and is a Professor of French at Oxford University.

Valerie has worked extensively on early modern Europe (especially France), especially on the transmission of medical knowledge about women and birth. In 2007, she published a bibliographical study of works on women’s reproductive medicine in French, Les Traités d'obstétrique en langue française au seuil de la modernité. Des "Divers travaulx" d'Euchaire Rösslin" (1536) à l' "Apologie" de Louyse Bourgeois sage-femme" (1627). (Geneva, Droz). It spans the century from the earliest printed obstetric manual to the first treatise published by a European midwife, and has become foundational for research in this field. Her subsequent book, a translation and edition of Pregnancy and Birth in Early Modern France. Treatises by Caring Physicians and Surgeons (Toronto, Iter Press, 2013), was awarded the Society for the Study of Early Modern Women’s prize for the Best Teaching Edition in the field of gender and women’s studies in 2013.

Valerie looks at ways to promote fruitful dialogues between literary specialists, social historians, historians of medicine and present-day healthcare practitioners. As a Mellon-TORCH Knowledge Exchange Fellow, she leads a project between The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities and the De Partu History of Childbirth Group. She regularly attends conferences and seminars fostering dialogue between historians and contemporary health practitioners, and also uses websites to engage with researchers from other disciplines and the wider public.

To find out more about Valerie Worth-Stylianou’s past and current projects please visit Birthing Tales and Birth through History.