‘French dog!’: interpreting insults on the streets of London

This piece is reblogged from the Voltaire Foundation. Please visit their blog for more information, upcoming posts and an archive of previous posts.

‘French dog! ’: interpreting insults on the streets of London

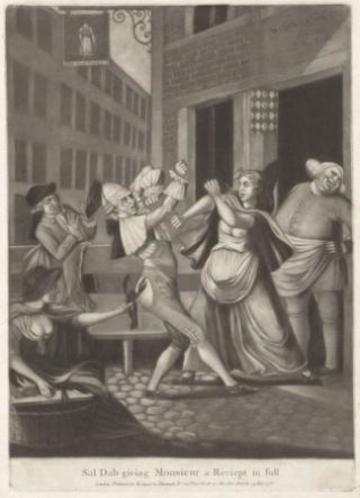

In light of the recent events and the emergence of questions around British openness (or lack thereof) towards a cosmopolitan culture and foreign nationals, it is interesting to step back in time and observe what kind of reception foreign visitors to England enjoyed in the past. Even for the most anglophile early modern visitor, three aspects of any trip often remained problematic. First, the terrible physical discomfort of crossing the Channel. As the gallant poet Le Pays would have it, it is preferable to look at the sea in a painting than in real life, when one is in danger of joining in the choir producing a ‘symphony of hiccups’ on board. Then there is the ‘gastronomic’ shock of English cooking; and, last but not least, the insults foreign travellers (and French people in particular) systematically received from many locals, mostly from the lower classes, and particularly in London.

The most traditional insult, ‘French Dog!’, actually seems to go back all the way to the period of the Avignon schism. The author of the first French travelogue on England in 1558, Estienne Perlin, complained that he was often called ‘or son ou vilain fils de p.tain’. Huguenot visitor Misson de Valbourg, who fled France in 1685 and then sketched an idealised image of England as a land of hope and freedom, provided a much more favourable portrayal of the English. Still, he felt compelled to add that this positive image accurately describes only those who ‘hadn’t always been rotting in England’, but have seen something of the world. Voltaire was insulted on the street, but carefully avoids discussing this experience in the Lettres philosophiques. Montesquieu’s posthumously published ‘Notes sur l’Angleterre’ features some comments regarding unpleasant attitudes on the part of locals. These words inspired some scholars to categorize this text as anglophobic – no doubt an excessive statement, as many other opinions he expresses in the same text were clearly positive.

For French visitors who were not particularly favourable to England, xenophobic insults were a convenient tool to prove that the English notion of ‘freedom’, even though it seemed attractive in theory, was nothing but arrogance. Others attempted to explain the differences between the attitudes of what many of them perceived as the ‘mob’ on the one hand, and the excellent welcome they received from the often strongly francophile local elites on the other; they suggested that there might be ‘two nations’ living side by side in England. This led some to conclude that the true national character could only be found amongst the elites; others suggested that the brutality of the ‘mob’ in fact represented quintessential Englishness, the elites having been civilised by their contact with Continental culture. From the 1760s onwards, following Rousseau’s ideas (such as those in his chapter on travels in Emile), a new approach arose, which saw the true national character residing in the popular classes, but only when far away from the negative impact of large cities: thus, ‘true English people’ reside in the countryside.

During the last decades of the Ancien Régime, a new interpretation emerged for the insults encountered in the streets. In some ways parallel to Edmund Dziembowski’s suggestion that French anti-English feelings and propaganda could have contributed to the creation of a French national identity, some French visitors suggested that English xenophobia, however unpleasant an experience, could be a noteworthy (and even positive?) phenomenon. In his book Observations sur Londre celebrated by the Royal Censor as an ‘eternal antidote against the depraved and contagious morals of our so-called Philosophers’ for deconstructing the myth of English superiority, Lacombe suggested that the disappearance of xenophobic insults is a sign of England’s downfall, as these were manifestations of a powerful, true national character.

The unpleasant English attitudes that many foreign visitors encountered, and often reported, became for the French public part of a set of well-established ideas, related to the practice of a travel to England. As I have argued in Philosophies du voyage: visiter l’Angleterre aux 17e-18e siècles, the systematic study of the variations in the interpretation of such ideas allows for a better understanding of the complexities and uses of this travel phenomenon. The same event or the same place (such as the Monument of the Great Fire of London and its inscriptions) could receive radically different presentations depending on the personal profile, agenda and experiences of the visitor.

See also https://cultureoftravel.wordpress.com

Dr Gábor Gelléri