Georges Rouault and the Prodigal Son

Presentation by Dr Jennifer Johnson at the 'Grace' Seminar

On 01 April 2021 Dr Jennifer Johnson (History of Art, Oxford, JRF St John's College) gave a wonderful presentation to our "Grace" seminar - on Georges Rouault and the Prodigal Son. The lunch-time seminar was very well attended and generated a stimulating discussion. Here is Jennifer's account of the talk...

In 1929, the Ballet Russes performed what was to be Diaghilev’s final commission, The Prodigal Son, with music by Prokofiev and choreography by Balanchine. In addition, Diaghilev asked the painter, Georges Rouault to design the sets and costumes.

Rouault was an interesting choice. Born in 1871 at the height of the violence of the Paris commune, Rouault identified himself throughout his career as a ‘painter of darkness’. He trained with the great symbolist painter Gustave Moreau, but Rouault quickly went on to develop an intensely thick way of painting, applying paint in heavy daubs and mark that give the surface a dense, even ossified appearance. Around 1910, he began to eschew the conventional use of an easel, preferring to work at a table – and on multiple works at once. In part, there was a practical side as he often worked on paper then mounted on canvas, and paper worked upon vertically would never have supported the weight of paint he applied. But it is also part of major theme in his work which is the physicality of painting itself, and an embrace of the materiality of his craft.

In one sense, this might seem immediately un-graceful – there is a certain elegance of gesture associated with the artist stood before the easel brush in hand. The image of the painter embroiled in paint on a horizontal platform (which of course we will see much of later in the 20th century amongst matter painters such as Jean Fautrier or abstract expressionists such as Jackson Pollock or Helen Frankenthaler) is quite different. But Rouault is working in a moment where the idea of meaningful expression is being rethought in numerous ways and that he is particularly engaged with the idea that ‘grace’ itself, understood as a form of higher understanding or illumination, is to be found within material practice itself – and not beyond it. This is a huge shift from a key idea that the arts might approach or even embody an idea but that somehow their physical form itself gives way or is somehow passed-through as the revelation of that idea emerges.

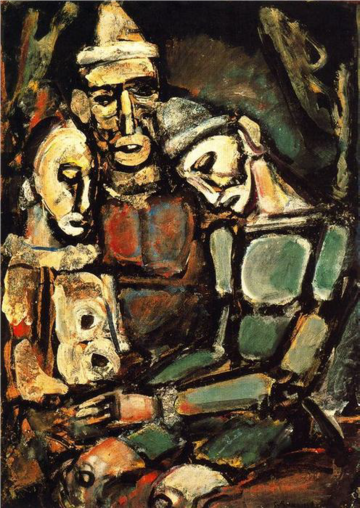

Le clown blesse (1932) by Georges Rouault | Photo credit: Philippe Migeat

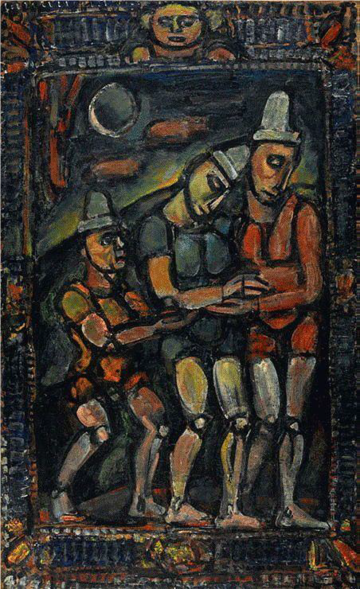

Trois Clowns (1917) by Georges Rouault | Image from wahooart.com

In her lecture, on April 1st, as part of the Dance as Grace: Paradoxes and Possibilities, Dr Jennifer Johnson explored the ways in which Rouault’s work complemented and to some extent structured the way in which the ballet emerged. She argued that the influence of Symbolist theatre, and particularly the radical marionette theatre in Paris (most notably that associated with Alfred Jarry), informed Rouault’s interest in immobility and the articulated form of the marionette body which his costume design transferred onto the dancers themselves. In addition, Rouault shared with Balanchine an interest in Byzantine art and in the Russian idea of the holy fool, which is prevalent amongst Rouault’s numerous paintings of clowns.

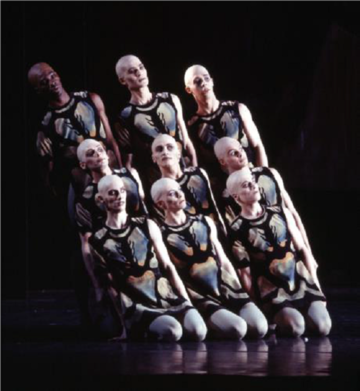

In Balanchine’s choreography, the arrangement of the dancers moves as if from composition to composition – and this is perhaps particularly challenging to the idea of grace – in that there is an angular, even jarring quality to the movements themselves. But at the same time, as in Rouault’s compositions, there is an emphasis on pattern: we see the shapes made by the bodies dominating the space – gesture is hugely important but it is enacted at a bodily form or pattern level, and not at the level of individual or even naturalized expression. These are ‘types’ not personalities – and in the language of the symbolist marionette they are highly effective in communicating from ‘within their own aesthetic world’.

Scene from ballet 'The Prodigal Son' | Choreography by Balanchine | Photo credit: Bill Cooper

Scene from ballet 'The Prodigal Son' | Choreography by Balanchine | Photo credit: Bill Cooper

Scene from ballet 'The Prodigal Son' | Choreography by Balanchine | Photo credit: Bill Cooper

Scene from ballet 'The Prodigal Son' | Choreography by Balanchine | Photo credit: Bill Cooper

The trajectory of the ballet also traces that other sense of Grace in Rouault’s oeuvre. The son, fallen amongst the siren’s troupe and seduced by the siren appears irretrievably ‘lost’. He morphs as he is stripped and left against the tree into the Christ-like figures of Rouault’s clowns. And here the importance of lighting is striking to the creation of the armatured-body effect on stage, even as the body falls.

What is key to Rouault’s work is the way in which various aesthetic and expressive elements are integrated – and the same thing at work in this ballet. In the lines of the costumes, the white clown-like tights of the siren, and the way in which the dancers articulate shape after shape, forming patterns – through all these elements an intense, perhaps remote but certainly charged aesthetic grace emerges: drawing together these parts into an emotive whole.

You can find more information on Dr Jennifer Johnson's book 'Painting and Materiality' on her page on St John's College.

Knowledge Exchange project page of Professor Sue Jones Dance as Grace: Paradoxes and Possibilities

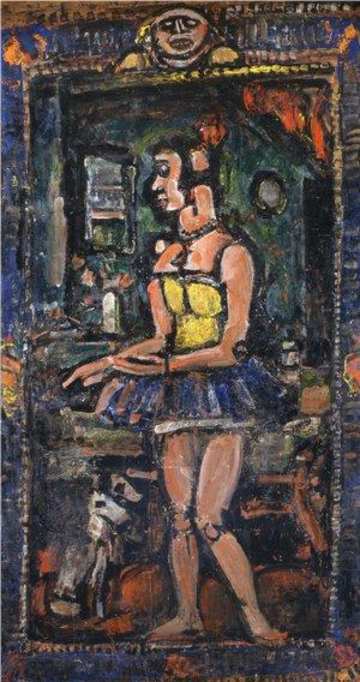

'Danseuse' (1939-1944) by Georges Rouault. Photo: Jean-Louis Losi (image courtesy of the Fondation Georges Rouault)