How can sensitive topics be shared publicly?

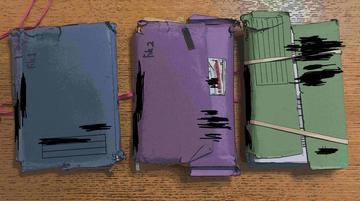

Yacoub’s case files at his lawyer’s office Image credit © Andreas Bjorklund

Yacoub* arrived a young and hopeful man in Britain in 2007. He had been forced to leave his home in Kuwait, but without citizenship or official papers to prove his identity. He is a member of the stateless Bidoon community (from the Arabic: bidoon jinsiyya, ‘without nationality’) which since the 1960s have asserted a right to Kuwaiti nationality. The Kuwaiti authorities, however, claim that most Bidoon are foreigners pretending to be stateless in order to access rights, benefits and privileges available to Kuwaiti citizens.

In the first decades after Kuwait’s independence in 1961 the Bidoon were able to live fairly regular lives. They could work (often in the military), study, access free medical treatment and other basic social services. But by 1986, amidst several local and regional political crises, they had become officially designated ‘illegal residents’ and their lives severely restricted. When Iraq occupied Kuwait in 1990-91, the Bidoon were collectively scapegoated as collaborators. Around half of the 260,000 Bidoon in Kuwait were forcibly displaced and prevented from returning to their homes.

Yacoub’s family was amongst those who were able to stay, but like many others he grew up in uncertainty. With no legal access to work and rent, would his family become homeless? Would he be able to go to school the next day, or would he be expelled for not having the right papers or enough funds to pay the tuition? Would his family risk detention and deportation? Anxiety and disappointment persisted as he came of age. A promising footballer, he had been prevented from playing at the elite level because of his status as a Bidoon. How was he to start his life when everything could be taken away at any moment?

Then, somebody offered to help him travel to Europe and seek asylum.

Today in Britain, 16 years later, he finds himself in a similar situation. He has had multiple rejected applications for asylum and other types of leave to remain. Without a legal status he faces severe restrictions on his ability to find accommodation and access medical care. Without documentation he is not allowed or able to work, study or pursue his dream of one day becoming a pilot. And without a passport he is unable to return to Kuwait or try to start a new life anywhere else.

And he is not alone. There are thousands of Kuwaiti Bidoon forced migrants in Britain, many who spend years in irregularity as their applications are rejected.

Model by community member (Image credit © Dea Gjinovci)

Drawing by community member (Image credit © Dea Gjinovci)

Spreading awareness about sensitive topics

Since 2016, I have been conducting ethnographic research to understand how people attempt to exit what seems to be never-ending limbo. From the outset of the research, two prominent and interrelated themes arose. The first is the many tolls on mental health burdening people in the community regardless of their specific legal status: asylum-seeker, refugee, British naturalised citizen, temporary resident or undocumented person. Secondly, community members often express concerns, fears, frustrations and disillusion regarding their ability to seek treatment, move forward with their lives or even talk about, let alone organise around, these issues.

In such circumstances, what happens to the body and mind? What can be done to address this type of suffering? And how can these difficult topics be sensitively talked about whilst caring for people’s well-being and privacy?

Over the years I have discussed these questions with Nasser Al-Anezy of the Kuwait Community Association (KCA), an organisation for Kuwaiti Bidoon in the United Kingdom. According to Nasser and many other community members, there is a dilemma between, on the one hand, raising awareness around issues facing the Kuwaiti Bidoon, and, on the other, finding effective ways to do so when there is much communal hesitation to engage with these issues publicly. People noted that while mental health issues are important and need to be normalised, they can also be stigmatising and put people at risk. Not all stories need to be shared.

The KCA and I planned to systematically gather testimonies on mental health issues through a workshop. Whilst planning, community members suggested to limit attendance to ensure those present felt comfortable to discuss sensitive topics. To share the issues and themes raised, an appropriate format and media would be needed. Community members felt that visual material should be used to accompany attendees’ anonymised statements with redacted details to describe their feelings and experiences.

This raises a dilemma. In academic research, journalism, the arts and human rights work it is common to anonymise personal details to protect the privacy of persons who generously share information about their lives, especially when they may be vulnerable or at-risk. At the same time, details are not trivial or easy to alter. Personal narrative stripped of their individuality risks rendering refugees what anthropologist Liisa Malkki calls ‘speechless emissaries’, indistinguishable and helpless victims whose lives are simplified to fit the expectations of researchers, aid-workers and the wider public in host countries. Even in this blog post, complex individual persons are diluted to become ‘community members’, ‘attendees’, and ‘participants’. Our aim was therefore to bring together people to share, listen and creatively think about how to relay sensitive experiences and stories.

We therefore began collaborating with Dea Gjinovci, a documentary film maker whose previous work includes ‘Wake Up on Mars’, a feature-length film about ‘resignation syndrome’ among child asylum-seekers in Sweden and the documentary short ‘Dustaway’ about undocumented cleaners who developed life-threatening illnesses from working at Ground Zero in New York City. Dea’s role in the workshop was to run a creative session in which attendees produced artwork and miniature models to be used as visual material in lieu of photos or video recordings that could identify vulnerable and at-risk participants who wish to remain anonymous.

In this way, stories divorced from the names, faces and voices who told them can come to life as human stories. Through an artistic medium and working with their hands, workshop attendees could explore ways to tangibly portray their thoughts, feelings and dreams without having to reveal personal details or examples from their own lives.

Model by community member (Image credit @ Dea Gjinovci)

Model by workshop attendee (Image credit @ Dea Gjinovci)

Workshop discussion and creative storytelling

With support from TORCH and the European Network on Statelessness the Knowledge Exchange Partners held a workshop in February 2023 at the University of Oxford. Five community members with experience of forced migration attended, including Yacoub. They were men born between the 1960s and mid-1990s, with various legal and family statuses as well as educational and organisational experiences.

Those participants who wished gave individual statements and took questions from the attendees. Otherwise, there were organic round-table discussions for the whole workshop, and sometimes amongst smaller groups. Several key themes emerged during the day:

- Mental health issues can lead to physical conditions that restrict people’s ability to manage daily tasks, plan routine activities or larger projects and enjoy themselves or find pleasure in life. Most attendees expressed that they had personal experiences of physical ailments arising from stress because of their forced migration, sometimes compounding earlier problems from Kuwait.

- There are severe difficulties to maintain healthy relationships with loved ones due to long-term family separation during the asylum process. There are also difficulties in adapting to new and different circumstances in the UK, sometimes as a result of multiple moves within the country which adds to feelings of rootlessness. It can be hard to form or strengthen new relationships as health issues can sometimes inhibit confidence, energy or interest.

- Mental health is identified as a reason for limited communal engagement and has implications for the potential to collectively plan and carry out various initiatives and activities. There was consensus that many in the community feel compelled or only have the energy to focus on personal or immediate family problems as opposed to wider issues facing the community as a whole.

-

Existential anxiety, especially aging, preoccupies both the younger and more senior community members. Several attendees spoke of a ‘lost’ or ‘stolen’ youth, or of the life of their children passing by in absence. Attendees of all ages mentioned declining health accelerated due to years of stress and mental health issues. There were also feelings of incompleteness and rupture with their homes in Kuwait. ‘We have been cut out from our environment,’ as one attendee put it, ‘and our children’s link to our country, our social norms and the Arabic language.’

The Knowledge Exchange Partners also teamed up with two clinical psychologists and researchers at University College London, Dr Francesca Brady and Sana Zard, who attended the workshop. Francesca and Sana were present to offer general information about mental health conditions of concern in the community, what type of treatment can be accessed in the UK and to offer support. They also presented observations and reflections from their ongoing research and clinical work through the NHS to which Kuwaiti Bidoon are referred for treatment. They related how of the nearly 40 people so far referred, only one had completed the two-phased treatment plan. A range of factors could be influencing the low follow through in treatment plans:

-

Insufficient knowledge on the part of clinicians of the wider context facing Kuwaiti Bidoon forced migrants in the UK.

-

Sensitivities around discussing mental health and it becoming known that a person is seeking treatment or experiencing mental health issues.

- Sentiments among those referred that the many legal and practical problems they face take precedence, leading to individual health not being seen as a priority, particularly when there are caring responsibilities for children or relatives.

Community members who had had experience with mental health service provisions in the charitable sector expressed mixed feelings at their reception and treatment (none had been seen at Francesca and Sana’s service). It was mentioned that some charitable non-governmental organisations had taken a long time to respond to requests for referrals or had even rejected to offer treatment due to limited resources. There was also a feeling that mental health services were only ‘dealing with symptoms rather than causes’. One attendee described it as follows:

‘Mental health service has been very compassionate and supportive in the past, but I was disheartened because there was only so much they could offer when I reached out to them on different occasions. I feel it is futile because whatever support is available so far seems to be designed to help me cope rather than overcome mental and psychological trauma.’

Moving forward

The workshop attendees have continued to share their reflections on themes brought up in the workshop’s round-table discussions and individual presentations. These thoughts, reflections and testimonies, along with the artistic content created in the workshop, are being prepared for publication via an online exhibition by the Knowledge Exchange partners. There is much diversity among the Kuwaiti Bidoon community members who have participated in this project as individuals whose histories, backgrounds, personal circumstances, opinions, beliefs and life trajectories vary greatly. There is also much they share in having had experiences of forced migration as stateless persons. In coming together to discuss mental health issues in their community, they also share a desire to share these sensitive issues.

Yacoub and the others wish to make it known what they are experiencing. Working with them we hope to find one effective and ethical way to do so.

Human X, the online exhibition, will be published during the summer 2023.

*Yacoub is a pseudonym.

Find out more about the Human X: portraying mental health amongst stateless forced migrants of 2022-23 Knowledge Exchange Project here.