In The Blood

This blog was originally posted by FIG in July 2021.

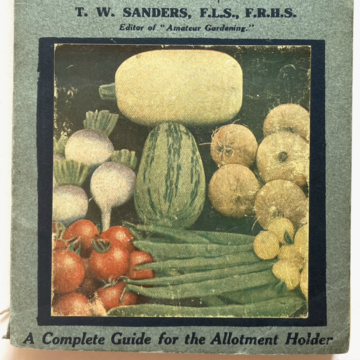

One of the sources for developing the 1918 Allotment is Kitchen Garden and Allotment: A Simple Practical Guide to Home Food Production by T.W. Sanders. This slim volume first came out during the Great War and does what it says on the tin. It covers all the essential information that someone with access to a plot of land would need to be able to grow basic food crops. Sanders was a great proponent of amateur gardening and published over 70 books on the subject. His Encyclopaedia of Gardening (originally published in 1896) is still very much in use today. His attitude to gardening is exemplified by his editorship of Amateur Gardening magazine for 40 years as well as co-founding the National Amateur Gardening Association. Sanders did not believe that gardening should be formal but instead something that anyone ought to have access to and be able to practice.

This is the spirit that is alive and well on allotment sites across England. While carrying out my research on urban gardeners over the last few years, I have lost count of the number of times a keen allotmenteer has said to me ‘I wish everyone could do this.’ There is a real generosity of spirit that allotmenteers show in their wish that everyone should be able to benefit from being outside, from being part of a community of growers, from being able to get their hands into the earth.

Allotmenteers’ warm invitations made me wonder how they became allotmenteers and indeed how they learned to garden. The answers were fascinating. Many people could not really remember how they learned, they regarded themselves as great experimenters. They talked of being people who were happy to try things out and learn from their failures and work through their mistakes. There were also a notable number of people who learned as Sanders most likely did ‘at their parents’/ grandparents’ knee’. Sanders’ mother was a keen gardener and although he did not explicitly make the link – it is highly probable that she imparted the skills that allowed him to get an apprenticeship with an old gardener at a relatively young age.

Following Sanders’ book has been a fascinating journey through gardening history. Chapter Two on Manure and Fertilisers, for example, shows the continuations of, and breaks from particular gardening practices. Animal dung, bone meal and seaweed are still commonly used on allotment sites that I have had the pleasure of visiting or cultivating. What is less common is the use of oyster shell and leather parings. One fertiliser that he proposes that drew my attention was his detailed description on how to prepare blood.

Blood meal as it is known in the gardening world is rich in Nitrogen which makes it a useful fertiliser. It is also linked to deterring deer and rabbits and so is a gentler way to deal with ‘vegetable foes’ as Sanders calls them. However, too much blood can ‘burn’ plants, amongst other unwanted effects – hence Sanders’ careful and detailed instructions on how to use it.

I became curious about the blood that was spilled on the battlefields on the Western front during the Great War and its effect on the soil. Could it be that it acted as a fertiliser and supported the growth of the scarlet corn poppies (Popaver Rhoeas) that were a common sight covering places where soldiers had fallen? The poppy went on to become a symbol of remembrance and thanks to John McCrae’s poem In Flanders Fields is inextricably linked with the great sacrifice of life during World War One. The reason that these flowers grew so prolifically on the otherwise barren soil of battlefields, is at once more practical and gloomier. Poppy seeds are triggered to germinate by light and so do particularly well in soils that have been disturbed. The churning to the soil caused by shelling and incessant bombardment during World War One created the ideal conditions for this beautiful flower to grow.

Soil, blood, seed – Let me draw Strength from you. Let it be enough – Emily Whitman

As I continued to work with Sanders’ book – thoughts of World War One swirling around in my head – I began to see the words on the pages differently. On page 45 of the edition that I am using I ‘found’ this poem amongst the lines about how to cultivate beetroot:

Thrust

the blade down deeply

Press back

the handle

Twist

Although the poem startled me and reminded me of the use of bayonets – it also spoke to me of the response that Mother Earth can have to the violence that we enact upon her.

Even gardening which we think of as a peaceful activity has within it practices of aggression for the more-than-humans we garden with. I am thinking, here, for example of the worms I have accidentally split in half while digging the ground.

Sometimes, these acts are more deliberate, and yet Mother Earth often still chooses to return us to a place of hope. During World War One we blew up the ground and spilled her children’s blood all over her – she replied with a burst of astonishingly beautiful flowers.

I have been writing poems as part of the process of developing the 1918 allotment but did not expect the Sanders book to be a poetic guide as well as a horticultural one. I will be sharing some of these poems at works in progress readings on the site when we open up for visits in July and August. There will also be a chance to participate in activities and hear from other poets who write about gardens and World War One. Do sign up to the Fig newsletter here so that you will get to hear about the dates as soon as they are released

This blog was originally posted by FIG in July 2021.