Misaligned Hope and Faith in Healthcare

Steve Clarke is currently Crawford Miller Visiting Fellow at St Cross College. He is also a Research Associate of the Wellcome Centre for Ethics and Humanities, Uehiro Centre for Practical Ethics and Faculty of Philosophy at the University of Oxford.

This seminar was based on work-in-progress that I am conducting jointly with Justin Oakley from Monash University, as well as Jonathan Pugh and Dominic Wilkinson from the Oxford Uehiro Centre for Practical Ethics, on ‘Misaligned Hope and Faith in Healthcare’. The work is funded by an Australian Research Council Discovery Grant on ‘Religion, Pluralism and Healthcare Practice: A Philosophical Assessment’.

It is widely presumed by healthcare professionals that it is important that their patients possess hope for a successful treatment. The key reason for this widespread conviction is that hope has motivating qualities. Patients who possess hope of successful treatment will be motivated to cooperate during healthcare procedures, to take medication, undertake programs of exercise, stick to any prescribed dietary restrictions, and so on. Patients who lack hope may well lack the motivation to do any of these things, and their health is liable to suffer, as a result.

While patient hope is important in healthcare, not just any hope will do. Patient hope needs to be based on a realistic understanding of the chances of success and failure of a particular healthcare procedure – it should not be ‘false hope’. There are two reasons why. First, the informed consent process requires patients to understand sufficiently the risks involved in a healthcare procedure before that procedure can be permitted to take place. Second, it is important that patients are prepared for the possibility of an unsuccessful outcome. A patient who has not adequately considered the chance of a healthcare procedure being unsuccessful is less likely to make any needed preparations for the possibility of life after the procedure, or indeed death, if there is a significant chance that this may be an outcome of a particular unsuccessful healthcare procedure. To quote Benjamin Disraeli, a patient should ‘hope for the best but prepare for the worst’.

Religious faith is a key source of hope. Patients often report that they possess hope of a particular outcome because of their faith. However, religious faith can sometimes lead patients to have unrealistic expectations of the chances of a successful treatment, or to have hopes that are aimed at different goals than the ordinary goals of healthcare. Such situations are problematic because they can hinder rather than help patients. How should we respond to these situations? There are two very different sort of responses that are often articulated. Libertarians want to permit patients to make decisions to undergo medical procedures on the basis of any considerations, including faith-based hopes, on grounds of respect for freedom of choice. In contrast, rational interventionists want to restrict choices made on the basis of faith-based hope on the grounds that choices grounded in hope incorporate irrationality of a sort incompatible with autonomous decision making. Our research team aims to articulate a ‘middle way’ between these extremes and argue that patient decision making based on faith-based hope should be acceptable and permitted in healthcare when it conforms to norms of practical rationality. These norms allow patients room to make decisions to consent to undergo medical procedures informed by faith-based hope, but they do not involve endorsing each and every appeal to faith-based hope that patients may make.

At the core of the presentation were four case-studies describing actual patients whose faith had led to misalignment between their hopes and the ordinary aims of healthcare, as presented to those patients by healthcare professionals. The seminar was followed by a lively discussion led by two distinguished respondents, Joshua Hordern of the Faculty of Theology and Religion at Oxford and Mehrunisha Suleman of the Ethox Centre, also at Oxford. Both respondents welcomed the proposed approach to misaligned hope and faith in healthcare but pushed me, in different ways, to draw out connections between the ideas presented in the seminar and larger issues concerning religious belief and hope, particularly as these issues impact on healthcare.

The event was a good opportunity to try out ways in which philosophy, theology, and bioethics can work together, with each discipline pushing the boundaries of their own methodological approaches and traditions, to try to better understand the role, significance, and limits of hope and faith in healthcare.

Please follow the link to the seminar's recording.

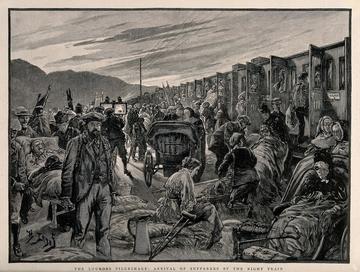

Image credit: The Lourdes pilgrimage: arrival of sufferers by the night train, H. Lano, Wellcome Collection