Of Course the Gay Has to Die: Why the Liberal White Audience Doesn't Get the Wound (2017)

(This article was first published in New Bloom and contains spoilers.)

See this post at our companion blog site - raceandresistance.com

THE MUCH-ANTICIPATED South African film of the year, The Wound, was officially released on the 27th of April, 2018, in the UK. On the 28th, the white South African director John Trengove came to Oxford and participated in a post-screening discussion panel at the Phoenix Picturehouse in Jericho. Many professors and students in Postcolonial Studies and African Studies attended, watching the film for the first time.

The film was much anticipated because it is indeed one of the very few films that deal with aspects of homoeroticism and homosexuality in traditional African communities, and before its general release this year, it had already been shown at various international film festivals—not only did the film open the Tel Aviv International LGBT Film Festival 2017, it was also selected as the South African entry for the Best Foreign Language Film at the 90th Academy Awards. Outside of the West, the film also participated in the 2017 Taipei Film Festival and received much praise for its “brave challenge against the taboos in black African culture”. It is worth noting that both Israel and Taiwan love to emphasize their image as “the most liberal and LGBT-friendly” country” in their respective regions.

Director John Trengove was awarded the Best New International Director at the 2017 Taipei Film Festival by Hou Hsiao-Hsien. Photo credit: 2017 Taipei Film Festival

Judging from the two-minute trailer, the film seems to contain many attractive “native” elements for this kind of international success: a secretive Xhosa initiation ritual presented from an insider perspective, a posh city boy from Johannesburg sent to the community who uncovers its queer undercurrents, a steamy homosexual sex scene in the lush grassland in the mountains, and most importantly, a seemingly confused protagonist caught between tradition/homoerotic love in secrecy, and modernity/homosexual identity risking exposure. Such central conflicts of identity are quite common in many non-Western queer films; just think of Ang Lee’s 1993 film The Wedding Banquet for example. Therefore, while all these elements come together to boost the international marketability of the story (together with all the journalistic capital it gathers via the trouble it had had with traditionalist groups and the authorities in South Africa), the anticipation for most of us concerned about queer postcolonial cultural representation is how the film may surprise us by subverting such Western expectations of anthropological voyeurism and modern identity struggle inflicted by Westernization.

Does the film succeed in achieving such subversions? Yes, it does, and it does so in the very last five minutes. The drastic twist at the end is essentially the genius of the film but it is also worrying that its abruptness may make a liberal white audience too confused to understand the subversion and its importance. Right at the beginning of the film, we are invited to enter straight ahead into the voyeuristic space of ritual-watching: the traditional Xhosa rite of passage—Ukwaluka(circumcision and initiation into manhood)—is performed on a group of young men covered in white powder wearing nothing except a thick blanket. While performing the circumcision, the older men ask, quite forcibly, the young men to shout loudly—“I am a man!”—under the public gazes of the others.

For the Western audience, the corporeal act of the ritual would naturally remind one of similar acts of circumcision common in some Christian communities while the hyper-masculine spectacle of initiation recalls the fraternity clubs on American campuses. These androcentric cultural traditions may well lead the audience to associate Ukwaluka with the negative impressions we have on homosocial patriarchy and toxic masculinity, and the film certainly does not shy away from such negative portrayals of the traditional Xhosa community in its story.

Many posters of the film feature the gay city boy Kwanda, who acts as the catalyst for the conflicts in the film. Photo credit: Film still

Indeed, as the plot of the film unravels, we find out that it is exactly this hyper-masculine setting that the central relationship in the story is situated in. The protagonist Xolani, a reticent young man with a melancholic aura of sentimentality, works in a factory in Queenstown but returns to the mountains every year to participate in the Ukwaluka ceremony as a khaukatha (mentor/caregiver). However, we soon learn that Xolani’s participation in the ritual is largely motivated by another important ritual between him and Vija, a handsome muscular khaukatha married with three children.

Every year, Xolani and Vija take part in the ritual as mentors and they would have sex during breaks without being seen by others. In this yearly ritual, they have managed to create a private queer space within a hyper-masculine patriarchal indigenous cultural structure. Indeed, rather than “closeted gays” as many Western media have labelled them, these two are queer—their homosexual acts have yet to become a fixated gay identity that can only exist in a binary social space of either/or, and instead they are merely taking advantage of the homosocial space of assumed masculinity to channel their desires for each other as “friends”, no matter how unsatisfying this “friendship” would later become for Xolani.

This queer ritual has worked fine till a new initiate (mentee) called Kwanda comes to the mountains, assigned to Xolani. Similar to most of the audience watching the film, Kwanda is the intrusive outsider and holds a set of liberal metropolitan values and only participates in the ritual passively and reluctantly. Sent down from Johannesburg, he is only there because his father thinks he is “too soft” and therefore can use some traditional Xhosa culture to gain some masculinity, which already reveals the divide between urban modernity and rural tradition, as well as the instrumentalist mentality the former has about the latter.

Kwanda stands out in the group of initiates not only because he is unapologetically gay but also because he is “the rich city boy,” which he does not deny either. These two identities then form an interesting tension for Kwanda’s positionality in the group: on one hand, due to his feminine and “faggot” look and behaviour, he often becomes the target of bullies; on the other hand, the other initiates inevitably express some bitter jealousy towards his middle-class city life and dare not bully him for real as he is well protected by the mentors. In one scene, a rural kid asks Kwanda “what phone have you got?” in front of the other initiates, and he answers “iPhone,” to which the kid then replies, “Why not Blackberry?” and thus reveals the rural people’s troubled materialistic aspirations. In another more explicit scene near the end of their ritual, the other initiates perform a form of quasi-ritualistic homosocial exhibitionism by showing their penal scars to one another, excluding Kwanda as he is a “faggot,” but one of them emphasizes again that Kwanda is a rich city boy while praising his own penis as “Mercedes-sized” in front of him. In other words, Kwanda’s gayness is inseparable from his urban middle-class identity, and this combination of power is in turn inseparable from the global gay culture growing in the South under the influence of Westernization.

The ritualistic intimacy between Xolani and Vija, often taking place in the beautiful landscapes of the mountains, recalling Ang Lee’s Brokeback Mountain. Photo credit: Film still from The Wound

Indeed, as the director also acknowledges in the post-screening discussion, as a representative of such Westernized middle-class gay culture, Kwanda is not really queer—his understanding of homosexuality is an either/or binary, and he cannot tolerate homosexual acts or love if they have not been through the process of “coming out.” For this kind of middle-class gay culture, the most important rite of passage is just that: coming out and be proud, be gay or be a coward. It also has to be noted that Kwanda’s firm belief in this binary gay logic is ironic, because even though he does not deny his homosexuality when the other initiates call him “the faggot,” it remains unclear whether he has come out to his father and the other elders in the village. Nevertheless, the gay rite of passage is at odds with the traditional rite of passage in the mountains, and this forms the central dramatic tension of the film. As many reviews have rightly pointed out, “the wound” in the title is polysemous and hints at the complex connections between the different characters. For Kwanda, the physical wound is inflicted upon him by patriarchal expectations via the agent of Xhosa tradition, namely Xolani, and in a perhaps accidental form of revenge, Kwanda inflicts a deeper psychological wound in Xolani through his condescending metropolitan gay values.

Portrayed as a rebellious spirit with perceptive eyes, Kwanda soon finds out about the secret relationship between Xolani and Vija and pressures Xolani to come out: “I know what your problem is. You are afraid of what you want.” Although Xolani has never responded affirmatively to Kwanda’s provocations, we are led to believe that this middle class gay logic of compulsory exposure and pride has gradually influenced Xolani, as in several scenes after this conversation, we see him asking for more recognition from Vija. He confesses to Vija that he could have chosen a different life in the city and yet he keeps coming back to the mountains because of love.

As an alpha male figure who is much more invested in the masculinist preservation of Ukwaluka, Vija seems to distance himself from Xolani after this, but when Xolani is confronted by two initiates about his “inappropriate” relationship with his “faggot” mentee, Vija immediately intervenes and beats the initiates in horrifying fits of violence. Soon after this incident, the film then presents its most sensual part—the intimate scene of the two men making out and making love by the beautiful waterfall (recalling Wong Kar-wai’s Happy Together (1997) as well as the watery intimacy in Barry Jenkins’s Moonlight (2016). Here we also reach the climax of the narrative as the two naked sleeping men are caught by Kwanda: as they exchange the homoerotic gazes of embarrassment and exposure, Xolani shouts “Run!” while Vija, who does not yet know about Kwanda’s knowledge of his relationship with Xolani, chases after him with supposedly violent intentions.

Kid: “What phone have you got?” Kwanda (nonchalantly): “iPhone” and this is one of the scenes that induced much laughter from the audience during the screening in Oxford. Photo credit: Film still from The Wound

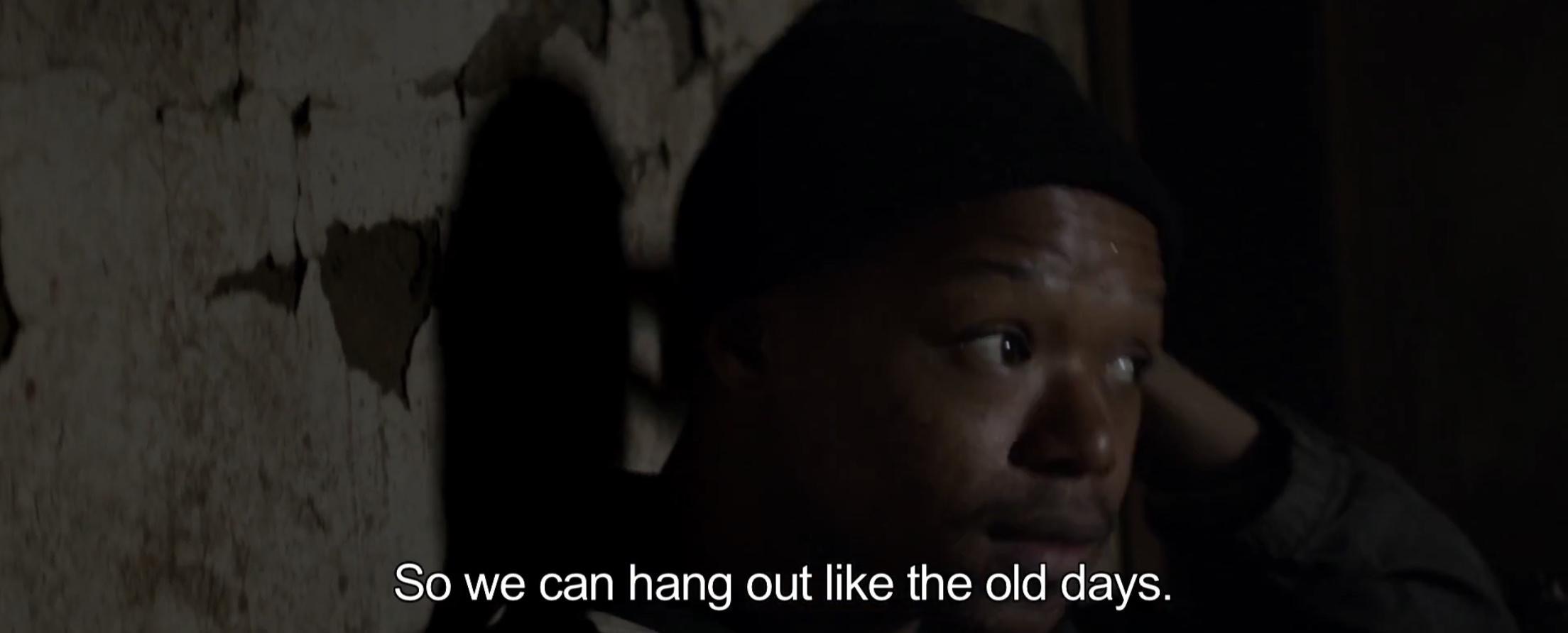

Then comes the eventful twists in the last ten minutes of the film. Kwanda is declared missing by the people in the village but Xolani finds him in the forest and walks with him to the highway, making the audience think that he has decided to go with Kwanda to the city and leave his “closeted relationship” behind. On their way to the highway, Kwanda keeps making condescending comments like “This is South Africa, not Zimbabwe…How can love destroy a nation?” and in the meantime bashes the Xhosa ritual as outdated and stupid. Here the real international aspect of the global gay culture represented by Kwanda is revealed: homonationalism, namely the use of gayness to construct a neo-colonial narrative of civilizational hierarchy in which the “progressiveness” of Westernized South Africa is reflected through the “backwardness” of its lesser African neighbours. Such homonationalism fails to remind us that most of the homophobic institutions in many African countries today are legacies of colonial rule. These problematic opinions, at least for some audiences with more postcolonial sensitivities, should make Kwanda very difficult to identify with at this stage despite the fact that he has always acted as our substitute and allowed us to have this voyeuristic outsider view of the Xhosa community in the first place.

At this point, I became increasingly uneasy sitting in the cinema. If Xolani goes with Kwanda to the city like this, the film will just be one of those tiresome tales of a Western(ized) young man going to a native traditional community to save those he deems as “oppressed” using his liberal modern values. However, what happens next in the film essentially sublimates the entire story towards a non-Western queer perspective. When they come close to a cliff overlooking the highway, Xolani suddenly pushes Kwanda off the cliff and kills him. The final scene of the movie then shows Xolani sitting in the back of a track alone, heading towards Johannesburg as the high buildings of the city move across the screen.

As many of the questions raised in the post-screening discussion show, many audience members were surprised and confused by Xolani’s murder of Kwanda, and one of them asked the director: “In a way the film is about the exposure of the secret relationship in the community, but (with Kwanda’s death) at the end, that secret is again hidden away, isn’t it?” Though it is hard to know what particular opinions this audience member holds about the “secret”—whether she thinks the ending is disappointing or not, the question does indicate an obsession with this binary between secrecy and exposure, closetedness and coming out, oppression and freedom.

Xolani confronted by two initiates about his “inappropriate” relationship with Kwanda. Photo credit: Film still from The Wound

This is a concern shared by almost all of the reviews of The Wound in Western media, and it fundamentally misses the point of the film. To be blunt, Kwanda is the only gay character in this film and he has to be killed because the middle class gay values he represents have always been intrusive, voyeuristic, alienating, and condescending. Kwanda’s fixation with gay authenticity essentially disrupts the homoerotic ritual of Xolani and Vija and his demanding attitude deprives Xolani of any agency to make decisions on his own calculations. Indeed, before Xolani kills Kwanda, he tells him, “He (Vija) has family and children, and you don’t think about that.” This statement demonstrates that Xolani not only despises Kwanda’s individualism but has always been fully aware of what loving Vija entails. As he told Vija in an earlier scene, it is not like he did not have the choice to leave him and live comfortably in the city—their yearly ritual of queer love has always been an informed decision of mutual consent and recognition, no matter how imperfect this queer love may be. Indeed, in the pragmatic worldview shared by many Third World countries, nothing can be perfect or taken for granted and making choices always means making sacrifices. The murder of Kwanda can therefore be regarded as Xolani’s rejection of Western middle class gay values and allows the film to shift the audience’s identification back to Xolani and make them reflect on his (and their own) positionality.

The ending scene is simply brilliant—after killing Kwanda, Xolani goes to Johannesburg anyway, and his melancholic expression is again full of troubled sentimentality and emotional ennui, echoing the beginning of the film when we first see him. This adriftness and loss of belonging is something quite universal that most queer people of color or queer people of the non-West may identify with. Even after rejecting the intrusive condescension of Westernized gay culture, Xolani cannot go back to the old ways of queer love in the traditional community anymore. If the other initiates already second-guessed about him being another “faggot,” the other members of the community may also become alert, and sooner or later his relationship with Vija will not be able to sustain itself. Once exposed, their secret queer ritual will lose its ontological basis and cannot continue to function without the compulsory conversion to either absolute heterosexuality (if Vija denies it and stops the ritual for good) or absolute homosexuality (if Vija scarifies his family and reputation to be with him). Therefore, self-exile towards uncertainty is the only way out of such a dilemma.

Xolani and Vija caught in the act, and this scene is added to the UK trailer while the earlier official trailer does not have it. Photo credit: Film still from The Wound

However, as the audience’s reactions show, it remains questionable whether this shift of identification and positionality can be effectively inflicted upon the liberal white moviegoers in the West. If the director does intend to inflict a “wound” on the middle-class gay mentality in the developed countries, as he declares, it is only successful if the audience is reflective enough to take this wound. That is to say, if they walk out of the cinema feeling pity for Kwanda (and his failed act of “liberation”) and sorry for Xolani and Vija (and their “closeted relationship”), then the film has failed its mission of subversion.

Moreover, the way the film is marketed in international festivals and cinemas—all those elements of “the spectacle of secret rituals of black Africa,” “oppressed sexualities,” and “the unravelling of queer love”—runs the inevitable danger of antagonizing traditional Xhosa culture. Rather than queering the initiation ritual and traditional Xhosa culture (though the film does occasionally hint at the blurry boundaries between homosociality and homosexuality in such masculine spaces), the film’s portrayal of this community remains largely negative. Not only is it seen as hyper-masculine, patriarchal, and oppressive, the community members also make frequent racially charged comments on the white people in the city but at the same time express their materialistic jealousy toward the lifestyle of the city people. Even though we should give the director a lot of credit for recruiting actors who have actually been through the initiation ritual (all of them went through Ukwaluka except Kwanda (Niza Jay Ncoyini) and many of the scenes in the film may indeed have happened in reality, its approach to the representation of this secret initiation culture and community mimics Kwanda’s unapologetic agenda of exposure and criticism.

To be clear, I am not saying that we should not criticize the negative elements of this traditional Xhosa culture at all, rather, what I want to stress here is the fact that such antagonistic portrayal in the film may not leave enough room for negotiation for a queerer understanding of this culture. Although the controversies over South African censorship of the film and the backlash from certain traditionalist groups later became one of the film’s attractions for the international audience, we do have to appreciate the director’s (and his Xhosa co-writers and collaborators’) courage to focus on such a topic. But as I emphasized in my question to the director in the discussion session, some of the backlash may not necessarily come from the traditionalists being hyper-masculine and homophobic but from their frustration about this public exposure of their secret/sacred ritual, which is tainted with the antagonistic portrayal of them as hyper-masculine, homophobic and even racist (thus becoming a tricky self-fulfilling prophecy of its own). Indeed, this intrusive and negative approach to Xhosa representation creates an ideological echo chamber for itself and its liberal (international/Western/white) audiences and does not leave much room for (the otherwise quite queer-able) traditionalists to enter the conversation.

The good old days of secret queer love cannot continue after exposure, as it relies on this very secrecy to exist. Photo credit: Film still from The Wound

For me, the last five minutes of the film is what prevents it from becoming simply a Xhosa language film made by a white South African director for an international liberal (and white) audience who would like to see themselves as sympathetic towards the “oppressed Other” in the dark middle-class space of Western cinema. But I do wonder, do those white people sitting next to me feel the same?

Flair Donglai Shi (施東來) is a DPhil in English candidate at the University of Oxford. His thesis focuses on the Yellow Peril as a traveling discourse in modern Anglophone and Sinophone literatures. His articles on postcolonial feminism, Chinese literature, and world literature have been published in many academic journals, including Women: A Cultural Review, CLEAR, Comparative Literature & World Literature, and Subalternspeak. He holds an MSt in World Literatures in English from University of Oxford and an MA in Comparative Literature from University College London. He is currently working on an edited volume in Ibidem's World Literature Series entitled World Literature in Motion: Institution, Recognition, Location.

----

Race and Resistance is always looking for new contributions to our blog. If you would like to write a piece, or if you have a response to a blog entry you have read here, please e-mail the blog editor, Annie Castro at anne.castro@mod-langs.ox.ac.uk.

The viewpoints expressed in Race and Resistance are those of the individual contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the University of Oxford.

Flair Donglai Shi

Race and Resistance across Borders in the Long Twentieth Century