Peggy McCracken in Oxford

Report on Peggy McCracken Lecture for OMS

The 2020 Oxford Medieval Studies Lecture was delivered by Professor Peggy McCracken on Animate Ivory: Animality, Materiality, and Pygmalion’s Statue. Read the reports on the talk by two doctoral students and watch the full lecture (scroll to the end).

***

Lesley MacGregor writes: On the evening of 23 January 2020, we were treated to a talk by Professor Peggy McCracken entitled “Animate Ivory: Animality, Materiality, and Pygmalion’s Statue.” McCracken is the Domna C. Stanton Collegiate Professor of French, Women's Studies, and Comparative Literature at the University of Michigan. Her approach to the Pygmalion story and its medieval adaptations is similarly interdisciplinary as she examines the intersection of material and metaphor, grounding them both in notions of animation and the human-animal relation.

Found in Book 10 of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, the Pygmalion story recounts how a sculptor carved a female figure out of ivory and, finding her more beautiful than any other woman, fell in love. He prayed to Venus who transformed the once hard and immobile statue into a flesh-and-blood woman. By so doing, McCracken noted, the sculptor’s passion for an ivory statue was transformed into marriage with an ivory-white woman.

Le Roman de la Rose, 14th c, Oxford, Bodleian ms. Douce 332, fol. 192

Throughout her talk, McCracken highlighted the material nature of the statue and the transformation it underwent. She focused on adaptations of the story found in the thirteenth century Roman de la Rose; the fourteenth century Ovide moralisé, and John Gower’s fourteenth century Confessio Amantis. Like Ovid, the medieval adaptations focus on the material quality of the ivory, praising its whiteness. McCracken argued that the insistence on the materiality of the statue not only emphasises the miracle that brought the object to life, but also draws attention to the work and skill of the sculptor. For McCracken, whiteness is a constructed characteristic; one that is borrowed from a material substance provided by an animal and shaped by a human hand.

McCracken engagingly took her audience on an exploration of this idea of whiteness and its relation to both the lifeless statue and the animated woman. Ivory was particularly appropriate for the statue, she argued, in both texture and tactility, because it evokes the feeling of skin in a way that stone cannot. The collagen remaining in the harvested ivory retains warmth from the hands that hold it thereby echoing the sculptor’s touch as well as his desire to feel flesh. The responsiveness of ivory as a material, despite the statue’s stillness, thus reminds us that it was once part of a living creature; that only through animal death can Pygmalion’s creation be brought to life.

As an essential feature of the statue, ivory likewise becomes essential to the living lady. While an appreciation for pale complexions corresponds to conventional descriptions of beauty found in medieval narratives, a comparison to ivory is rare. Thus by referencing the ivory-whiteness of the woman, McCracken argued that the translators sought to highlight the change from material to metaphor (ivory to ivory-whiteness), bringing our attention back to the material that is transformed and the craft of the sculptor.

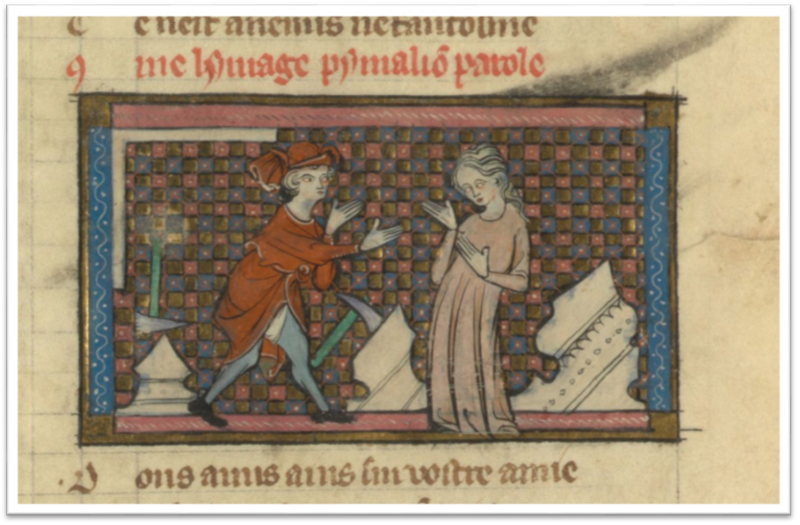

In the latter half of her talk, McCracken demonstrated how illuminators of medieval manuscripts focused less on the material of the statue and more on Pygmalion’s skill as a sculptor.

Le Roman de la Rose, XIVs, BNF MS. Français 19156, fol. 136r

Images, like the one above from the Roman de la Rose, insist that the miracle of enlivening an object requires work. Here we see the moment when the statue comes to life. The figures stand facing one another in the Pygmalion’s workshop, hands gesturing to each other, while around them are evidence of a sculptor’s trade: tools used for carving, debris, and unfinished stone capitals. The reminder that the ivory is a carved material makes visible the labor that produces whiteness. The Pygmalion story repeats the idea of whiteness as beauty and even life itself, but, McCracken claimed, simultaneously insists that whiteness is work and a product to be crafted.

McCracken’s talk is particularly relevant as the Humanities witness the so-called “animal-turn,” in which scholars focus more attention on the ways in which the lives of humans and nonhumans are mutually dependent. The popularity of the Pygmalion story experienced a marked rise in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries at the same time as the circulation of ivory increased with the opening of new trade routes to West Africa. Whether readers of the story would have equated the material of the statue with an elephant is unclear, but McCracken rightly emphasised that Venus enlivened an object that was previously part of a living creature. Whiteness, so praised for its material and metaphoric value, is only possible with an animal’s death. The story of Pygmalion is thus an apt reminder that animal products and the meaning we give them are grounded by the connection between life and death, animal nature and human skill.

Lesley MacGregor is a D.Phil candidate in the History Faculty. Her thesis examines the ways in which trials against domestic animals were incorporated and then managed by the criminal justice system in late medieval France.

***

Alex Lawrence writes: It was a pleasure to attend Peggy McCracken’s ‘Animate Ivory’, a highly informative talk which explores the material and metaphorical features and functions of Pygmalion’s ivory statue from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, and its subsequent medieval translations, linking the two aspects in challenging and imaginative ways. More broadly, Peggy’s work on animals and animality continues here in this new context to provide an insight into animal products, and the objects that are made from them.

As a doctoral student whose project focuses on the appearance of animals and animal-made objects in natural histories and travel narratives on the subject of the Americas in the sixteenth century (apologies to readers for my lack of medieval credentials), such methodological approaches are both innovative and inspiring. Not only can they illuminate our historical understanding of object-circulation and material economies, but, crucially, they underline the importance of the animal in textual production, from the very constitutive elements from which the book or manuscript is created, all the way to their allegorical and emblematic significance in literature. This work is fascinating, elucidating the complex relationships which have existed between humans and animals whilst converging critical perspectives in exciting ways. In short, we hope to see much more in the future!

Alex Lawrence is a first year D.Phil candidate in French in the Faculty of Medieval and Modern Languages, supervised by Wes Williams.

***

Watch the lecture by Peggy McCracken: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iUAQQ4IL3Tg&feature=youtu.be