Performance and Play: Family and Culture in the 18th Century

When you visit a country estate, do you ever wonder about the people behind the gilded frames? What were their interests, who were their friends?

Using material that we unearthed from the archives, we worked closely with our National Trust partners to bring the stories of the Yorke family and its rich literary heritage alive once more through an exhibition at Wimpole Hall: ‘Performance and Play: Family and Culture in the 18th Century’.

This article shares some of the highlights from the exhibition.

Union of Hearts and Homes

The Long Gallery at Wimpole Hall displays many of the Yorke family portraits, including the family patriarch, Lord Chancellor Hardwicke, the newly risen magnate who bought Wimpole Hall in 1739, his wife Margaret Yorke (née Cocks), and three of their seven children, Philip, Charles, and Elizabeth. They were a bookish family, and through the exhibition, we focused on the family’s literary interests and activities.

On either side of the fireplace hang the portraits of Philip Yorke, 2nd Earl of Hardwicke, and his wife, Jemima Marchioness Grey, painted in 1741 by Alan Ramsay to commemorate their marriage the previous year. The marriage between Philip and Jemima united two prominent Whig families, but, importantly for our project, it also brought together their family homes of Wimpole Hall and Wrest Park.

The Long Gallery at Wimpole Hall, displaying the Ramsay portraits of Philip Yorke and Jemima Grey. Image credit: Jemima Hubberstey

Despite the arranged nature of their union, the young couple’s shared love of books, history, and gardens provided a solid foundation for an affectionate and happy marriage. They formed their own literary circle at Wrest Park, collaborating with their friends to create Wrestiana, a private manuscript containing 30 years’ worth of poems, inscriptions, and play fragments.

Philip’s siblings, Charles and Elizabeth (whose portraits are also on display in the Long Gallery) were also prominent members of this circle and contributed to the Wrestiana manuscript.

Private collection. Wrestiana – the manuscript written by the literary circle that surrounded Philip and Jemima. Image credit: Jemima Hubberstey.

Excitingly, the exhibition unveiled two portraits recently returned from conservation: one of Margaret Yorke (née Cocks) and her daughter Elizabeth (who became Elizabeth Anson after her marriage to Admiral George Anson in 1748). The portrait of Elizabeth was only recently returned to Wimpole after a mystery donor stepped in at the last minute and saved the painting at auction.

The portraits at Wimpole recently returned from conservation. Image credit: The National Trust

The Gothic Tower

Among its various compositions, the Wrestiana manuscript contains inscriptions for the garden buildings at both family homes. Notably, this included the enigmatic inscription intended for the Gothic Tower at Wimpole.

Previously, the inscription had been attributed solely to Philip’s friend, the antiquary Daniel Wray. However, the manuscript is signed ‘W. P.’ – ‘W’ for Wray and ‘P’ for Philip. After examining the correspondence between the two friends in the archives, it became clear that Wray had written the inscription ‘to amuse the Family the half hour after supper’, while Philip had considerable input editing the inscription. The letters between the two friends therefore provide a fascinating insight into their literary collaboration.

The inscription has long baffled researchers. It opens with the Baron’s Wars, celebrating a moment in medieval history when powerful landowners rose up against their unpopular king. Although the first verse celebrates the ‘trial by sword’, the poem is complicated in the second verse as the scene shifts to modern times, revealing landowners wasting the day drinking champagne and reading books. Given Philip’s own interest in book collecting at Wimpole, this depiction is probably more playful than critical, and the poem concludes that having ‘Just Taste’ is as important as military strength.

This part of the exhibition complemented the National Trust’s recent restoration work of the Gothic Tower, which won a Europa Award in 2016.

View of the Gothic Tower from the exhibition panels at Wimpole. Image credit: Jemima Hubberstey

The Gothic Tower, Wimpole Hall. Image credit: Jemima Hubberstey

The Woodcutter

The final part of the exhibition focused on ‘The Woodcutter’, which was performed on site on the 12-13th June by our student performers. This was a later work, written by Elizabeth Hardwicke, wife of the 3rd Earl (Philip’s nephew). It was originally intended to be performed at Wimpole during the Christmas holidays of 1797, featuring Hardwicke’s own children, as well as their cousins, Thomas and Frederick Robinson (Philip and Jemima’s two grandsons).

Thomas, who was supposed to play the main character in the play, Hodge the Woodcutter, at the age of fifteen, described the excitement as he and his cousins prepared for the performance ‘to which we attached much importance’, learning lines and painting scenes. Sadly, the original performance had to be cancelled when his grandmother, Jemima Grey, died early in the year. However, sources suggest that the play was performed again.

Thomas was so inspired by these early childhood theatricals that later in life, when he inherited Wrest Park himself, he had a theatre built in the mansion. In 1849, he even staged ‘The Woodcutter’ again for his own grandchildren, recalling in his memoirs that to amuse the children, they had performed a piece ‘which had been written many years ago by the Dowager Lady Hardwicke and had been acted at Wimpole’.

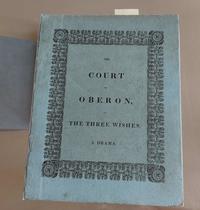

The exhibition also features The Court of Oberon (1831) – a revised edition of ‘The Woodcutter’ that Elizabeth Hardwicke had published in 1831 to be sold at a bazaar intended to raise money ‘for the succour of the distressed Irish.’

This version of the play was performed again by another later generation at Wimpole in 1851 and 1853 – which Elizabeth lived to see at the age of ninety!

The Court of Oberon, published in 1831. There was a later cast list included in this copy, so it is thought that this might have been the original copy that the family used for prompting. Image credit: Jemima Hubberstey

The exhibition has been a wonderful opportunity to work with our National Trust partners and showcase the research we have undertaken as part of the project, demonstrating above all the lost literary legacies of Wrest Park and Wimpole Hall.

The exhibition is running until the end of October, you can find out more here.