"We Have Always Been Here": Michael Dillon and Transmasculinity in Pre-War Oxford

Bio and Abstract: Jay Gilbert holds a doctorate in medieval linguistics and is currently researching queer terror and desire in the works of Robert Graves. They are a graduate of St Hilda's College, Oxford and Exeter College, Oxford, have tutored across various colleges and are currently managing communications at St Anne's.

This post describes the eye-opening experience of trans pioneer Michael Dillon, the first alumnus of St Anne's College, at Oxford and beyond. It considers the reactions of others to his transness and how these interlace with current concerns around identity and transition.

Keywords: Michael Dillon, Trans, Queer, Oxford, Transmasculinity

When LM Dillon left Oxford in 1938, his primary goal was to be forgotten.

This was not because his time here had been unhappy -- on the contrary, he had made, for the first time, friends in whom he recognised something of himself. He had developed, correspondence suggests, a valuable relationship with the then-Principal of the Society of Home Students, Grace Hadow, which would help change the direction of his life. He had petitioned tirelessly, and successfully, for the rights of women rowers to race upstream, side-by-side and over the same distances as men. Dillon had even won a rowing Blue.

The difficulty was, it had been for the women's team, and Dillon had come to recognise that he was not a woman.

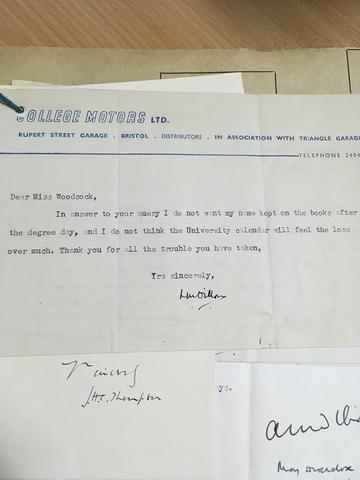

More problematically still, the all-female Society of Home Students -- now St Anne's College -- could not possibly have an alumnus. Dillon writes in his autobiography that "Oxford exerts a hold on her sons forever afterwards and a bond is wrought between them all,"[1] but in order to be viewed as the "Oxford man" he knew himself to be, Dillon's only option was to broadly erase his Oxford past. To a considerable extent, given how rarely his name is mentioned in the annals of Oxford history, he succeeded. However, his student file remains in the Library at St Anne's, and contains the following brief note:

"Dear Miss Woodcock,

In answer to your query I do not want my name kept on the books after the degree day, and I do not think the University calendar will feel the loss over much. Thank you for all the trouble you have taken,

Yrs sincerely,

LM Dillon."

The letter, though undated, forms part of a chain of correspondence whose dates would place its time of writing in February, 1942. Dillon writes on headed paper: the branding is of College Motors, the Rupert Street Garage where he was working at that time. Dillon was seeking his MA degree, but wished to acquire it in absence; due to the fact that he was not engaged in military service, a fee had to be paid for the privilege. For Dillon, though, graduating in absentia was not so much a privilege as a necessity. By the time this letter was written, Dillon had undergone not only hormone treatment but also a double mastectomy and the first known experimental phalloplasty. Passing fully as a man, it would have been impossible for him to present himself at Oxford to receive an MA under his birth name.

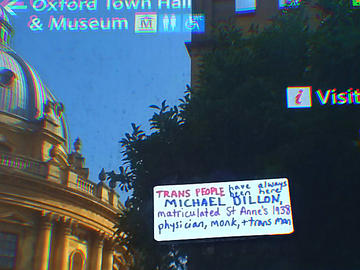

The battle over the rights of trans students at Oxford has been a hot-button issue over the past several years, fought in the media and made physically present and visible in Oxford through a stickering campaign which has seen pro- and anti-trans narratives plastered across phone boxes, lampposts and bus shelters. On one journey through central Oxford, I came across a sticker featuring Dillon's name, his affiliation as a St Anne's alumnus, and the phrase: "We have always been here." Dillon did suffer to a certain extent for his gender nonconformity at Oxford -- a journalist once printed a photograph of him, with his cropped hair and masculine rowing attire, captioned "Man or Woman?" which caused a mild furore. However, it is rather astonishing, set against the current backdrop, to note the ways in which his late-1930s transition was supported and, by many, unquestioned. As Dillon himself notes, the humiliation of being mocked as a member of the Women's Eight at Oxford was compensated for by the fact that, ten years later, he found himself stroking the Men's First Eight at Trinity College, Dublin, to enormous success.

Also in Dillon's student file at St Anne's is a letter he wrote to Grace Hadow, thanking her profusely for "putting [him] on to Zuckerman". Mr Zuckerman was, at that time, experimenting with endocrinology and had been injecting female rats with male hormones, and vice versa. Dillon tells Hadow that Zuckerman had been "helpful about the subject". He does not elaborate on what "the subject" was, but it seems possible -- even likely -- that Dillon had confessed to Hadow something of how he felt; certainly, she was able to infer that Zuckerman's work could potentially be of benefit to him. Very shortly after this meeting, Dillon was indeed prescribed male hormones in tablet form as an "official experiment." [2]

When at Oxford, Dillon was, by his own admission, completely open about his "troubles" to a friend at Teddy Hall, Bill, who "never batted an eyelid,"[3] and indeed helped Dillon acquire men's attire in order to attend University boxing matches, from which women were banned. Another of Dillon's close friends was "a girl...similar to myself" with whom he developed a "brother-relationship," taking boxing lessons and rowing intensively with her. On one occasion, Dillon attended the men-only Judo Club, whose members, upon identifying Dillon as his birth name, simply noted that "Your voice doesn't give you away."[4]

The loyalty of many of Dillon's friends -- and their willingness to accept him open-mindedly -- would likely be called anachronistic in a novel, but Dillon was continually lucky with his acquaintances. When, after the outbreak of World War Two, Dillon was working in a garage, he was unlucky enough to be early in his physical transition, such that his appearance was masculinising, but his colleagues knew he was "a girl really." A friend, however, whom Dillon identifies only as "G," stood up for Dillon in the face of teasing: "I said you really were a man and that had them puzzled. They didn't know what to believe then."[5]

Perhaps still more surprising to the modern scholar is the attitude not only of Dillon's friends and family -- while his brother never accepted Dillon's transition, his aunts came to -- but also that of total strangers. While the process of changing a gender marker is today extremely challenging and lengthy, Dillon was able to reregister as male and change his name on the basis of a letter from a doctor, declaring him to be "intersex." When he headed to the Labour Exchange to claim a new identity card, the clerk declared, '"We have had quite a lot of these applications," and made [Dillon] out a new card without batting an eyelid!' [6] Having now been reregistered as male, Dillon was then called up for the Army, and subsequently had a very similar experience when explaining the situation to the doctor at the recruitment office, who told him, "We've turned down a lot like you."[7]

After hormonal intervention, Dillon was soon passing fully as a man, something he called an "indescribable"[8] relief. A mastectomy and experimental phalloplasty streamlined this process further, and Dillon was, for the majority of his career, able to serve among men in close quarters without his secret being suspected. It is notable that when his past was finally revealed, it was due to a remarkable discrepancy between listings in Burke's and DeBrett's. Dillon's brother, a baronet, was childless. Where one of the listings continued to refer to Dillon by his birth name, the other judged that, as he was now a man, Dillon was his brother's heir, and listed him as such. Journalists from the Daily Express cabled the ship on which Dillon was serving to ask, "Do you intend to claim the title since your change-over?"[9] and Dillon's secret, in an instant, was laid bare.

While this incident was an enormous trial for Dillon, the continued accepting responses of those around him were a balm to him. His shipmates came "to the conclusion that I had had a raw deal and since they had liked me before and I had not changed overnight they saw no reason for letting it make any difference."[10] Meanwhile, scores of old friends wrote to Dillon, "offering their sympathy and saying what they thought of the press," while the Chairman and Medical Superintendent of Ellerman Lines, for whom Dillon was working, wrote to express support and ask him to stay with the company. While Dillon felt ultimately unable to do so, this outpouring of good feeling moved him deeply.

Michael Dillon is generally identified as the first person in the UK to undergo a medical female-to-male transition, but the reactions Dillon records towards his transness -- of support, acceptance, and indeed indifference -- make the veracity of this questionable. Evidently, the process of changing gender in the early 1940s cannot be straightforwardly mapped onto the same process today; but evidently, too, there may have been more trans students at Oxford, at any point in time, than are listed in the records. As our mystery stickerer aptly put it, trans students "have always been here."

[1] Dillon, Michael, Out of the Ordinary: A Life of Gender and Spiritual Transitions, Fordham University Press 2017, p. 74.

[2] Ibid, p. 90.

[3] Ibid, p. 82.

[4] Ibid, p. 82

[5] Ibid, p. 93

[6] Ibid, p. 101

[7] Ibid. p 101

[8] Ibid. p 100

[9] Ibid, p 214

[10] Ibid, p 215