Reading 1: Excerpt from Alan Bush, ‘Planning a Workers’ Music Festival’

Excerpt from Alan Bush, ‘Planning a Workers’ Music Festival’ (1936 - Never published)

When do workers’ music-organisations perform in public?

At political meetings and demonstrations, at concerts and entertainments, and at their own festivals.

What music do they perform? Sometimes their own music, sometimes the same as might be performed by other musical societies.

In this article we have to discuss

(a) the lines on which the programme for any particular occasion should be chosen;

(b) the way of presenting the items.

Different occasions require different fare and treatment. The various possibilities will be dealt with in turn. A few broad principles can, however, be laid down to start with:

1) Music should be treated as part of life, including political life, and not as something to be kept aloof from ordinary affairs.

2) The performers should be encouraged to take part in other activities of the working-class movement.

3) Performers and audience should be brought into close contact with one another as possible.

4) The audience should be made to take as active a part in the proceedings as is practicable.

5) Conductor and singers or players are members of one group and should behave accordingly.

Dealing with these five points in turn:

1) This is not the place for an enquiry into what art, what music really is. We know from experience that the performance of music does at least the following things: it stirs the emotions of the hearers and widens their range of thought and feeling, and it trains the powers of concentration of the performers, improves their health, increases their ability to express themselves, and it intensifies their consciousness generally. In fact it does some very useful things which make both hearers and performers more able to cope with life as a whole.

In this article we are approaching music from a practical angle and it will help us if we try to clear away some of the mistaken ideas people have about it. We will then see that music must necessarily be connected with life as a whole and is not something up in the clouds, far removed from all the other affairs of this world. Whether we are performing music or listening to it, or whether we are occupied in some ordinary pursuit such as sawing wood or doing housework, we are using our brains and our bodies. It is the same with composing. A composer uses his brains and body at one time to compose, at another to eat his dinner or read the paper. There is nothing more mysterious about composing than there is about else that we do; some people can learn to do it better than others but that applies also to knocking in nails or cooking a joint. It is true that in composing the mixing of the ingredients results each time in something new, different from previously composed works in a more fundamental way than then difference between one Sunday’s joint and another. But both are products of brain and body acting upon the materials of the world. To compose well certainly needs a lot of thought. But even the most absorbed composer can’t help thinking about other things as well at times and this is bound to affect his thinking when it comes to music. A composer might even shut himself up in a sound-proof room and in order to work, but he would not by this means exclude the rest of the world, because he must take

his brains in with him and with them the impressions of the world as he has known it which he has been storing up since birth.

Thus it is clear that music and the other experiences of life react upon one another. The reaction upon different composers takes different forms. Some try to create in their music a means of escape from the rest of life, others face the world and write their music accordingly, (though the works of composers even of this latter type are not necessarily all directly related to the real world.) Worker-musicians must keep these things constantly in mind when choosing their repertoire. A piece of music which has no direct bearing upon ordinary life as they are living it is neither better nor worse as music on that account, but its character in that respect may render it definitely suitable or unsuitable for performance on some particular occasion.

2) If music and the rest of life react upon one another, it is clear that music and politics can be brought into contact. The one can be made to help the other. It will make musicians more sensible and politicians more understanding and less opinionated. In the working-class movement above all musicians should be politicians. It will prevent them from developing their musical life out of touch with the requirements of their audiences.

This is not meant to imply that worker-musicians should give their public what it likes. They must study what it most needs. The class-conscious worker is in the vanguard politically, the worker-musician should be in the vanguard in his own sphere. Much of what the class-conscious worker says to his fellow workers is not at once acceptable to them, it upsets their preconceived ideas; in the same way the worker-musician will shock his public, will attack their preconceived ideas of what music ought to be like.

Worker-musicians are much more likely to gain a hearing for music among their comrades if they show themselves devoted to their interests in other ways. Conductors and choir-members should be active party members where this is practicable. When the rank and file party members know the worker-musicians as active politicians they are much more likely to encourage the musical side of the movement and to let it have its way in persevering with novelties which are at first unpopular.

In some cases where the choir or band is assisting at a political meeting it should be brought into as close a contact with the political side as possible. This can be done by arranging with the organisers of the meeting for someone attached to the choir to make a political speech in the course of which the choir’s work can be related in some way to the chief point of the meeting/ The conductor and one of the choir officials should sit with the rest of the platform.

3 + 4) The idea of the worker-musicians as the music-conscious vanguard is useful under this heading alone. The audience is composed of prospective worker-musicians. Everything should be done to make them feel at one with the performers. They must themselves become performers. The technique of teaching audiences a new song must be developed. An easy unison song is the only possibility at present. Copies of the words must be available and the audience can then be got to pick up the tune, line by line. Members of the choir can help by standing among the audience and leading the singing. Works should be written in which the audience has a special, very easy part, which can be learnt as the performance proceeds. By allotting to the audience phrases which recur or which are repeated immediately after the choir has sung them, or even words which are to be spoken in chorus instead of sung, an active participation of the audience is possible. If a group such as a Youth Group, can be got together previously for one or two rehearsals and can then be scattered among the audience success is assured.

The item should be introduces and to some extent explained by the audience by someone attached to the choir. This can be done quite informally or else a carefully prepared speech, even an argument between two members regarding the merits of the piece, could be given. The important thing in such an explanation is to point out the main ideas underlying the particular piece and say something about the general historical and social background of the composer, then to deal with the musical means employed to express the idea, and thus to show the connection between music and life. These explanations must be short and simple with very little in the way of technicalities. If two people were involved they could review the piece again after the performance and perhaps get members of the audience to express their views. This is only likely to lead to positive results after the audience has been roused to some show of enthusiasm. Otherwise the effect might be purely disruptive or it would fall flat. Comradeship between performers and audience must be established before criticism can yield useful results.

The more active a part audiences are accustomed to play the more concentrated will be their listening in cases where their participation in the actual performance is out of the question. They will know better how to listen and what to listen for. In this way they will begin to hear much more in music than before met their ears. The number of active worker-musicians will increase and the whole musical movement will gain in size and quality.

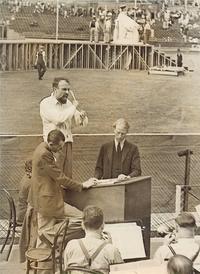

5) A choir or band must have both conductor and members. The parts they play are different and the conductor must at the performance stand in a prominent position in order that he may be clearly seen by all the singers. There is no need, however, for him to be singled out for attention in other ways. The choir need not be lined up breathlessly waiting for his entrance from the wings so that his appearance is a signal for special notice from the audience. He can perfectly well come on to the platform and sit with the male singers (or in the case of a woman-conductor with the sopranos or contraltos) until the performance begins. (An exception to this would be allowable where a long work, involving great nerve strain on the conductor, was to be given, and where it was thought necessary for the choir to take their places some time before the performance was due to begin, instead of making an orderly and carefully organised approach to the platform. This will be referred to later.)

There is also no reason why the conductor should be dressed differently from the choir members. If they all insist upon wearing full evening dress he should do the same. If not there is no sense at all in his putting on clothes which are inconvenient to conduct in, simply because at the present time theatre and concert-room conductors do the same. A difference in dress between conductor and members is a distinguishing mark between them, and for the conductor deliberately to choose clothes which are the hall-mark of bourgeois respectability can only have one object, namely to imply that the conductor would like to be taken for an upholder of bourgeois civilisation. In short, for the conductor of a workers’ music-organisations to wear glad rags is an absurdity’ (5).

Other ways in which a choir should however defer to judgement of the conductor, e.g. on music, yet they can also correct him in matters of politics:

‘A conductor is apt to look at the matter from a purely musical angle, and in view of the small number of tendencious works produced up to now of any musical value he may occupy the choir unduly with the music of an earlier period or with non-tendencious works of the present day. Here the political experience of the members and their desire to make music a force among the workers will act as a useful corrective’ (6).