The Art of Bearing Witness: On Visual Narratives, Comics Form, and Trauma

Blog post reproduced by kind permission of Robin Lindley and the History News Network.

Robin Lindley is a Seattle-based writer and attorney, and the features editor of the History News Network (hnn.us). His articles have appeared in HNN, Crosscut, Salon, Real Change, Documentary, Writer’s Chronicle, Billmoyers.com, Alternet, and others. He has a special interest in the history of conflict and human rights. This interview originally appeared on the History New Network website, and is reproduced here with their permission.

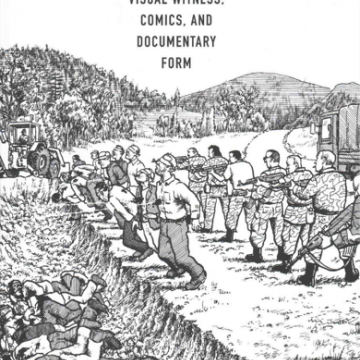

Professor Hillary Chute, a leading expert on the comic form, chronicles the history of graphic visual narratives and how they deal with trauma in her book Disaster Drawn: Visual Witness, Comics, and Documentary Form (Belknap Press of Harvard). She states in her introduction that the book “explores how the form of comics endeavors to express history—particularly war-generated histories that one might characterize as traumatic.”

In The Disasters of War, a series of unflinching prints, Spanish artist Francisco Goya vividly depicted the atrocities of the Peninsular War when Napoleon’s troops occupied Spain and brutalized its citizens from 1808 to 1814. He did not shrink from portraying the wounded and the dead, the cruel and the tortured, the mutilated, the grieving survivors. Goya proclaimed, “This I saw.” He had witnessed the depravity and horror of violent conflict as a first-hand “visual journalist.”

Goya is a precursor of today’s comic artists whose graphic narratives tackle the trauma of war and other consequences of human destructiveness.

In her book, Professor Chute explains how comics art, in an era of film, video and photography, has become a powerful form for bearing witness and engaging history with a series of frames and the interweaving and accumulation of visual and verbal responses. She traces the origins of today’s popular, long-form graphic novels on trauma to Goya’s print work and, before that, to seventeenth-century French artist Jacques Callot’s images of the savagery of the Thirty Years War.

Professor Chute describes the resurgence of the narrative visual form in the twentieth century in the work of artists from Winsor McCay and Otto Dix to Philip Guston and Robert Crumb. She then details the evolution of graphic nonfiction works since World War II. She examines at length the work of three major graphic comic artists who have addressed modern war: Keiji Nakazawa who survived the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and recounted his experience in I Saw It and other pioneering manga works; Art Spiegelman who based his awarding-winning Maus on the experiences of his family during the Holocaust; and Joe Sacco, a self-described “comics journalist,” who has reported on wars in the Balkans, the Middle East, and beyond in his graphic works of reportage.

Critics have praised Professor Chute’s book for its exhaustive research, original insights on literature and history, innovative critical analysis, engaging writing on trauma and witness, and profound understanding of the depiction of human suffering and sorrow.

Hillary Chute has taught at the University of Chicago and Harvard University and is currently Professor of English, and Art + Design, at Northeastern University. She teaches on comics and graphic novels; contemporary fiction; visual and media studies; gender and sexuality studies; and literature and the arts; among others. Her other books include Graphic Women: Life Narrative and Contemporary Comics; Outside the Box: Interviews with Contemporary Cartoonists; and Comics & Media: A Critical Inquiry Book (co-ed. with Patrick Jagoda). Professor Chute was also associate editor of Art Spiegelman’s MetaMaus, which won a National Jewish Book Award, among other prizes. And she has written for many publications including Artforum, Bookforum, The Believer, and Poetry.

Professor Chute generously responded by email to a series of questions on her background and on Disaster Drawn.

Robin Lindley: You are a leading expert on cartoonists and graphic nonfiction, Professor Chute. You have interviewed the most acclaimed artists in this field today. How did you come to focus on the art and artists of this form?

Professor Hillary Chute: Unlike many people I know, I started getting interested in comics as an adult—specifically, as a PhD student in English. I had no idea when I started graduate school in 1999 that I would wind up writing on the medium of comics, although I always was interested in the question of how narrative aims to express and register history.

I read Art Spiegelman’s Maus for the first time in a graduate course called “Contemporary Literature” in the year 2000. I became fascinated by Maus: fascinated by how it worked so well as a handwritten narrative that moves in words and images; fascinated by the dichotomies it pressurized (I remember reading a historian quoted in an academic essay claiming he wouldn’t touch Maus with a ten-foot pole, and yet Spiegelman argued for its status as nonfiction); fascinated by how it portrayed collective and personal trauma in the past and in the present. That was 17 years ago and I haven’t stopped being fascinated by Maus and even though I’ve now worked on a book about Maus with Art Spiegelman, I still feel like there’s a lot for me to learn from that book: every time I re-read it I notice something new.

Because I was so gripped by Maus, and how compelling and unusual it felt to me, I started looking for more nonfiction comics narratives—and I found a lot of them. Many more than I expected! A whole world opened up.

Eventually as a graduate student living in New York I met Art Spiegelman, after writing an essay about Maus online that he read. He invited me to a cocktail party at his house to celebrate the 25th anniversary of RAW, the groundbreaking magazine he and Françoise Mouly started in 1980. We stayed in touch and eventually after some great, animated discussions, mostly about our shared interest in comics form, he asked me work with him on the book project MetaMaus, which Pantheon published in 2011. We worked closely together for about six years on that book, and through Art I met many of the cartoonists whose work I had explored for my dissertation on nonfiction comics—and those who created work of which

I was simply a huge fan: people like Lynda Barry, Aline Kominsky-Crumb, Charles Burns, Chris Ware.

I was also a freelance writer at the time, and I met Joe Sacco—a central figure in my scholarship—when I wrote a short piece about him in the Village Voice. I met Alison Bechdel when I interviewed her for a feature I wrote on Fun Home in the Village Voice. I appreciated that these people created work so sophisticated and also so versatile that I could write about them in the Voice, or other mainstream venues, and also in scholarly essays.

Focusing on specific artists—and understanding their connections to each other—also drove me to organize the “Comics: Philosophy & Practice” conference at the University of Chicago in 2012. Seventeen of the world’s top cartoonists came to the conference, and the idea was to put them in conversation with each other, with professors and curators moderating. I wanted to have an academic conversation featuring the artists themselves, talking to each other about their shared contexts and concerns, rather than presenting academics explaining their work. The whole conference is archived in the Critical Inquiry issue on “Comics & Media” and on that journal’s website.

Robin Lindley: Are you an artist as well as an academic? Do you have a background in art and art history as well as literature?

Professor Hillary Chute: I care a lot about the art world, have friends in it, and have participated in some performance art pieces by the German artist Tino Sehgal (at the Marian Goodman Gallery and at the Guggenheim Museum), but I myself, alas, don’t create comics or any visual art, despite having collaborated on one short piece with Alison Bechdel, titled “Bartheses,” which was published in Critical Inquiry in 2014 (it’s a series of gag strips about Roland Barthes and the covers to famous Roland Barthes books, such as Mythologies).

My scholarly training is in literature, but I read a lot of art history and art theory—and visual theory in general—from when I was a doctoral student on forward. Because there was no critical canon, I was lucky to be able to feel that I could draw from many different disciplines to get the histories and vocabulary I needed to discuss comics. That’s part of what I appreciate about the form of comics: it is as pertinent to art and art history departments as it is to literature departments. One of my favorite ways to think about the form is that it is “productively awkward.” I guess one could also say “awkwardly productive.” A current passionate interest, and hopefully someday new essay or book project, is about the overlapping worlds of comics (meant for circulation in print) and fine art (meant for museums, galleries, collections).

I recently gave a gallery talk at the New Museum on the artist Raymond Pettibon, one of the main figures, along with South African artist William Kentridge, who has called attention to drawing as a newly important practice and object of fine art. Pettibon’s first mature work was a comic book called Captive Chains. There’s a lot of crossover with comics and fine art—we saw this also this year in the huge, acclaimed Kerry James Marshall retrospective at the Met.

Robin Lindley: Your recent book Disaster Drawn presents a history of how artists have depicted war and other disasters. What sparked this volume on “documentary comics” that deal with violence and trauma?

Professor Hillary Chute: I wanted to work backwards from the present to account for the emergence—or, rather, the re-emergence—of drawing as a form of bearing witness to history. I was fascinated by the fact that comics could represent world-historical disaster so movingly, and from an angle that felt fresh, but I knew that the kind of work I admired, by cartoonists like Art Spiegelman and Joe Sacco, a so-called “comics journalist,” didn’t come out of a vacuum.

I had read about and heard contemporary cartoonists mentioning artists such as Goya, with his nineteenth-century Disasters of War etchings, as a direct inspiration. In Disaster Drawn, I wanted to take the time to actually understand and meaningfully explain how works like [Joe] Sacco’s Footnotes in Gaza (2009) and Goya’s Disasters of War (created in the 1810s) share an idiom, and share specific aesthetic techniques, such as an approach to visual composition within the frame.

I wanted to create a longer historical trajectory for comics than people might typically expect. What does it mean to make an historical image by hand—whether by etching or by drawing comics—rather than “taking” an image? In Disaster Drawn, I group together hand-drawn images—specifically those meant for print—from across centuries, to reveal how drawing is an index of intimacy, immediacy, and crucial self-awareness in word-and-image works that bear witness to violence.

I also ask why comics is a form that is so popular now, after the age of the camera. In my view, the trauma of World War Two, in which conventional forms of expression came to seem inadequate to express human atrocity, and the highly televisual and photographed Vietnam War that followed, allowed the hand-drawn form of comics to reinvent cultures of expression. In 1972 both Keiji Nakazawa, a Japanese Hiroshima survivor, and Art Spiegelman, a Polish-Jewish immigrant to the United States whose parents both survived Auschwitz, created some of the very first meaningful nonfiction comics from opposite ends of the globe: Tokyo and San Francisco.

Something was happening in the 1970s to those who were directly affected by the war: they were finding new—and in this case, older—forms to register the violence that had devastated their families. And their work took off.

Robin Lindley: In your book, you explore “visual-verbal” witness to trauma and war, and a “golden age” of this form of documentary witness in graphic nonfiction in recent decades. How would you describe the themes of your book to an interested reader?

Professor Hillary Chute: Historical, collective trauma, and how to record it, is a big theme of Disaster Drawn. The work I analyze in Disaster Drawn has both words and images—I’m interested in how trauma inspires hybrid work that is hyper-aware of how it communicates. This is work in which words alone would be insufficient, and images alone would be insufficient.

The combination of the words and images allows meaning to be created in their interaction, or even in their disjunct. And all the work in Disaster Drawn is motivated by collective violence and its aftermath. For the printmaker Jacques Callot, who was born in Nancy, the capital of Lorraine, it was the Thirty Years’ War—his series of etchings from 1633, The Miseries of War, was published in the middle of that war. For the painter and printmaker Francisco Goya, it was the Spanish War of Independence that began in 1808 against the French, part of the Napoleonic Wars. His Disasters of War series of etchings was conceived of in 1808, the year the Spanish pueblo rose up against their occupiers—a violent action met with great violence in return. For cartoonist Keiji Nakazawa, it was the U.S. dropping of the atomic bomb on his home city in 1945 during World War II that inspired his comics. For Art Spiegelman, it was his Polish-Jewish parents’ survival—or inability, ultimately, to survive—Nazi death camps also during World War II.

In the wake of widespread violence, people struggle and often succeed in inventing or reinventing modes of expression to accommodate the ravages of history. This is why I wrote in the book that post 9/11, we are living in a “Golden Age” of documentary. That terrorist attack, especially in its manifestation as an unfolding media event, and its global aftermath, have created a new dispensation toward documentary across the board—and not just in film and television. In comics it shows up all over the place, in comics about 9/11, like Spiegelman’s In the Shadow of No Towers, and the graphic adaptation of the official 9/11 Commission Report, and also in the expansion of comics as a form of documenting a wide range of events all over the world.

Robin Lindley: You provide historical context for contemporary graphic nonfiction with your description of the work of Jacques Callot who depicted the carnage of the Thirty Years War and Francisco Goya who captured the atrocities of the Spanish War of Independence. You see Callot and Goya as “artist reporters.” Goya said he was a horrified witness. How does their work compare to what photojournalists and graphic artists do now to document traumatic events?

Professor Hillary Chute: I’ve been happy that recent writing has freshly acknowledged how profoundly important and influential these artists are—especially today. Jed Perl wrote a fantastic piece in The New Republic on Callot in 2013; he wrote that Callot, though not well known, “[ranks] among the peerless image makers and storytellers of European art.” The war correspondent Alissa Rubin wrote in the New York Times about Goya’s Disasters of War in 2014: “As someone who has covered wars closely over the course of 14 years, I found the engravings a true revelation.”

Both Callot and Goya created works involved in what Perl calls an ethics of vision. For me, this has two aspects, at least, that are enduringly relevant and meaningful. The first is that in both Callot and Goya’s etchings series, there is no politics that sits on the surface; neither series is polemical in that way. And that’s exactly what the “miseries” and the “disasters” of war create: a world pervaded by violence from all sides. In some of Goya’s most effective compositions, viewers can’t tell from a pile of corpses whether these corpses are French or Spanish. The victims are brutalized and also brutal; so are the perpetrators. Violence is all-consuming and endemic.

Bearing witness to that is, as you note, truly existentially horrifying; and harder than picking a side for whose suffering to reveal. In these works, suffering is everywhere. They bear witness to human capacities in both admirable and truly terrifying iterations but they are not polemical.

The second is that Callot and Goya’s prints not only bear witness to the collectivity of violence, but they also are about looking. In Callot’s works crowds assemble to witness brutal punishments. Many of Goya’s captions highlight the act of looking: “One cannot look at this”; “This I saw.” In that way these works suggest viewers be self-aware of themselves as viewers, and what it means and feels like to witness violence even at a remove.

Although there are so many stunning examples of photojournalistic images that take one’s breath away, for me it’s a categorically different kind of project: these images present a sense of their own transparency. Hand-made images as opposed to one’s hand-“taken” with cameras don’t offer the same sense of providing access to the real. They are much more self-reflexive, self-conscious. Their subjectivity sits on the surface. To me this is a good thing, this self-awareness about what and how we access history. It by no means indicates less of an investment in accuracy, but it is a different idiom of expression. And it is shared by contemporary cartoonists today.

Robin Lindley: What else did you learn about Callot and Goya?

Professor Hillary Chute: Fascinatingly, both Callot and Goya had court careers, but both produced these important works about war uncommissioned, on their own initiative, outside of the court system.

Callot was the official artist to the court of Lorraine, an independent duchy between Germany and France. But the Miseries of War was a work he took on independently, as Goya also took on the Disasters of War independently. Callot began the Miseries of War after refusing the French king’s request that he etch the siege of Nancy, his birthplace and the capital of Lorraine, in 1633.

Goya had a fascinating career because he was a royal court painter. He did a lot of different kinds of work in his life. Even within the medium of painting, he produced many different kinds of images in different genres, including portraits that exalted patrons and the court, and famous history paintings like “The Third of May 1808.” He used his skills as a printmaker for projects outside of the purview of the court—for his own aesthetic experimentation and pleasure. This work, as in Los Caprichos, his first suite of etchings that includes the celebrated “The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters,” often explored dark and satirical modes. It’s out of this idiom—the idiom of Goya the artist working on solely his own terms, with images and his own inscriptions—that The Disasters of War springs.

Goya conceived and completed the etchings for The Disasters of War over years, starting in 1808, and they were not published in his lifetime, although he created instructions for how they should be assembled and printed. They were first published after his death. There has been plenty of speculation as to why; I imagine that the displeasure he suspected they would cause, especially to the court, has to have been a factor.

Robin Lindley: It seems a “golden age” of comic books and then graphic novels ensued after the Second World War. Why did this form of drawn communication grow in popularity in an age of film, photography, television, and recently, internet and video?

Professor Hillary Chute: The Golden Age of comics is generally thought to date from the invention of superheroes in 1938, which contributed massively to the popularity of the comic book, to the mid-1950s, when the establishment of a censorship code for the content of comic books, the so-called “Comics Code,” harshly restricted the kinds of stories and images that were then flourishing, such as horror comics, from mainstream publication.

Comics were enormously popular during World War Two because superheroes joined the war effort, fighting Nazis and U.S. enemies in the comics. They galvanized support for the war, even before the U.S. officially entered the war, and they contributed to patriotism abroad, since U.S. military abroad consumed large numbers of comic books. One quarter of all books shipped abroad to soldiers during World War Two were comic books. (The historian Bradford Wright has an excellent and illuminating chapter in his book Comic Book Nation [Johns Hopkins UP, 2003] on comic books and World War Two.)

When the Golden Age ended amid concerns about comic books’ effect on youth, it took a while for the so-called Silver Age to begin, and for the graphic novel field to develop. I believe the Vietnam War and the counterculture of the 1960s and 1970s influenced both trends.

In the Silver Age, superheroes re-emerged as neurotic, as insecure, as sulky teenagers even—hence the Marvel superheroes like Spider-Man who are still popular, and relatable. The previous image of the ultra-masculine superhero felt outmoded; people, especially young people, were anxious and it was OK for their superheroes to reflect that too.

That anxiety was also reflected in underground comics, which operated outside the mainstream publication and distribution channels—and is where so-called “graphic novels” took shape. Because in the underground there weren’t commercial pressures to publish in a conventional format, or to publish conventional stories, cartoonists started using comics to write longer, personal stories—ones that didn’t, perhaps, seem to have commercial value but which changed the field forever.

Justin Green wrote the first autobiographical comics story in 1972: it was 44 pages. That same year, he edited an underground publication that had Art Spiegelman’s “Maus” story in it: a three-page precursor to the longer work. Real ideas were coming out of comics that were seen as a left-wing, anti-mainstream form.

Despite whatever leaps are being made in screen technology, there has always been something urgent and immediate about putting pen to paper, especially in the context of resistance or speaking truth to power.

Robin Lindley: You note that comics expand the range of documentary and offer a new way of seeing historical events. How does that work? Can you give a couple of examples of what you mean?

Professor Hillary Chute: The most direct way to put it is that because comics is drawn, and explicitly framed—as when frames that represent moments of time sit next to each other on a page—it is able to present a rich picture of the past, in both words and often quite-detailed images, and it is also able to call attention to its own procedures, its own point of view, so to speak.

I’ve written that while all media do the work of framing, comics does it in a literal, material way. The late John Berger, whose writing on drawing is a big influence, noted that drawing has a quality of becoming rather being. That doesn’t mean that documentary comics aspires to any less truth than a documentary film that appears more “objective.” It’s only that in drawing—to quote another of my favorite writers on drawing, Michael Taussig—“history is repeated in slow motion and the clumsiness of the artist adds to this seeing seeing.” To me, the awareness of the body of the artist that is manifested in the drawn line adds to the richness as opposed to distracting from it.

On a related note: comics is an art of memory, as many prominent cartoonists have noted. Details can be recreated in drawing that no longer have any physical corollary and are hard to otherwise reproduce. In Keiji Nakazawa’s drawn account of surviving Hiroshima, for example, readers get a powerful view of what the atomic bomb blast looked and felt like from the point of view of a six-year-old whose world was suddenly shattered as he walked to school on August 6, 1945. From the survivor, we get both the interior trauma—visual representations of what that experience was like in the mind of that one person—and also the exterior one, say, what swaths of the city of Hiroshima looked like when it had been flattened.

Comics—or anything of a similar serial nature, like a group of etchings by Goya about the Spanish War of Independence— also solicits a certain amount of imaginative activity from the reader to fill in the blanks between frames. I like to say that comics is paradoxically moving and still at once. It is not a time-based art, like film or video, in which a viewer relinquishes the pace to the director and is swept along from start to finish (and the frames move so quickly, 24 frames a second, that they create the persistence of vision effect). Neither is it exactly static, like a news photograph appearing alone with a caption on the front page of the New York Times, or a history painting by Manet. And it’s not linear the way most prose is; reading a page of comics is a much less linear experience than reading a page of any novel or nonfiction book. It’s not as directed in terms of the kind of reading it suggests. It is the only form I know of that routinely juxtaposes frames next to each other, so that the reader encounters them and produces meaning out of figuring out their relationship.

Robin Lindley: Much of your book is devoted to three prominent graphic or comic artists: Keiji Nakazawa, Art Spiegelman, and Joe Sacco. Like their precursors, they write and draw about war and the resulting trauma of war. How would you compare the ways they deal with the trauma of war in their art?

Professor Hillary Chute: Nakazawa, Spiegelman, and Sacco are creating word and image narratives with a lot of specificity linked to named individuals: Nakazawa created comics about his own experience, and his family’s, during the atomic bomb blast and its aftermath; Spiegelman interviewed his father Vladek extensively about his experience; Sacco, as a reporter, interviews individuals about their experiences and then these people are rendered very precisely and named in Footnotes in Gaza and his other works of comics journalism.

In Callot and Goya’s cases, in which the violence of war is chronicled in a word-and-image form, there is plenty of specificity—about modes of warfare, about the behavior of soldiers and armies, about the spectacle of violence, about fear and the effect of its ubiquity on civilians and soldiers alike. There is something concrete to be learned about the Thirty Years War and the Spanish War of Independence. Yet there are no named individuals pictured in their works. I think of this as a mode of collective visual witnessing: the individuals pictured could be anyone, in a sense, which is part of the fear and horror they can provoke. One striking similarity across all of these works, though, is that none of them propagate an ideological strict “us vs. them” point of view, however profoundly terrible the violence they chronicle is.

In Callot and Goya’s compositions, one often has trouble figuring out who the victims and who the perpetrators are; they make these categories feel null.

The similarity is that all of the works show how violence is endemic; how it drives and affects all sides of war. In Nakazawa’s work, there is critique of the Japanese imperial pro-war policies in World War II, in addition to attention to the profound tragedy of America’s decision to drop the atomic bomb. In Spiegelman’s Maus, some Polish gentile characters, along with German Nazis, act harmfully to Polish Jews; some are very kind and helpful, at great risk to themselves. “Good” and “bad” doesn’t cut across the national/ethnic lines that would seem to nominally shape the conflicts driving war.

Robin Lindley: Nakazawa survived the bombing of Hiroshima and vividly portrays the horror of bombing and its traumatic aftermath in I Saw It and other works. He was a first-person witness. What strikes you about his portrayal of a trauma he suffered directly?

Professor Hillary Chute: What’s so striking about Nakazawa’s work from 1972 is, first, that it offers a rare sustained look into an on-the-ground visual perspective of a person who himself has survived the atomic bomb blast. For an American audience, and also for a Japanese audience, this was rare. That was rare in the 1970s and still is rare. (For many Americans, for instance, John Hersey’s excellent prose work Hiroshima, a work of reporting that reveals the stories of various people affected by the bomb on that day, is the closest similar work, but it comes filtered through a Western voice, unlike in Nakazawa’s work).

Second, as an account in words and pictures, it portrays individual trauma—what the child saw (hence the forceful declarative of the title, I Saw It), heard, and experienced, what that felt like from his point of view. It gives us a sort of phenomenology of trauma—access to how this was registered in one person’s young body and consciousness.

Robin Lindley: You are an authority on the work of Art Spiegelman and his moving Maus books that deal with his father’s memories of the Holocaust—and his own response. He does not flinch from portraying the gruesome reality of the death camps and other atrocities. He uses cats and mice as the characters rather than human figures to represent Nazis and Jewish victims. How does his use of animal figures affect the power of his work? Does it make trauma somehow more palatable to readers?

Professor Hillary Chute: There’s a whole chapter on the use of animals to figure people in the chapter called “Why Mice?” in MetaMaus, so it’s a really important question. I’ll offer my own take here (and anyone interested in his own take in his own words might want to read MetaMaus).

For me, it is one of the central reasons Maus is such a powerful work. This figuration does a lot in the text. The expressive, minimalist mouse faces could be “us,” whoever we are as readers. The abstraction of the animal metaphor—which is a visually figured metaphor in Maus—allows readers to enter into the work through its stylized simplicity. Yet the “mouseness" of the mice isn’t something that also enters into the text through prose. The characters are figured as animals to readers, visually, but these characters know themselves as humans. They talk about their fear of rats, for instance. They represent real, named, specified people.

So the animal metaphor is a feature of the text that exists purely on the visual level—one might say it’s extra-semantic. That abstraction, to me, does not mitigate the horror. The panel of Hungarian Jews—drawn as mice—being burned alive in a pit is terrifying; the stuff of history and of reader nightmares. It rather signals to readers how difficult it is to represent the past with anything approaching verisimilitude—while aiming to be as accurate as possible.

This is one of the things comics is best at: that ability to be accurate and self-reflexive at once. Further, the animal metaphor in Maus is re-signifying the Nazi propaganda that posited Jews as vermin to be eradicated. It’s inhabiting and destroying that de-humanization.

Robin Lindley: In contrast to Spiegelman, Joe Sacco works—I think—in the tradition of “artist reporters” such as Callot and Goya. He has covered bloody conflicts in Bosnia, Gaza, and beyond, and created a unique 24-foot long drawing of the 1916 Battle of the Somme. He draws realistic figures and graphically portrays their anguish, their wounds, their deaths. How does his approach and his effectiveness in his communication form differ from Nakazawa and Spiegelman? Do you have a preference among these artists?

Professor Hillary Chute: It’s impossible for me to have a preference among the contemporary creators I research! All of their work has been so field-defining, globally, in twentieth-century culture—Nakazawa’s Barefoot Gen, also based on his experience surviving the atomic bomb, is the first long-form manga ever to have been translated into English, in 1978, for instance. Art Spiegelman changed the comics field forever with Maus. And Joe Sacco re-created the category of the “artist-reporter”—a category in which Callot and Goya belong—for contemporary times.

I agree with you wholeheartedly that Sacco works in that tradition; in fact, putting his work in conversation with artists from centuries before was one of my central aims in Disaster Drawn. The difference with Sacco is that he does long-form word-and-image works; while Goya’s series Disasters of War is lengthy at 83 etchings, Footnotes in Gaza is 418 pages.

Like Callot and Goya, but unlike Nakazawa and Spiegelman, Sacco has no familial connection to the accounts of war he presents. He uses similar techniques, but he is a reporter, a journalist. Neither Nakazawa nor Spiegelman, although they produce nonfiction, would identify primarily as a reporter.

Robin Lindley: Most of the powerful work you discuss in your book can be seen as antiwar because it stresses the cruelty, the trauma, the very real human cost of war. Maybe once an artist reveals the trauma of war, the work can’t help but raise doubts about war. How do you think these depictions affect readers? Did you find works that you’d consider militaristic or “pro-war?”

Professor Hillary Chute: There are plenty of pro-war American comics, especially from around the time of World War Two and the Korean War. There were pro-Nazi comics. And although it might seem like a stretch, the large number of superhero comics historically and today are about war—even if that war is intergalactic, say. Recently, for instance, the Marvel-produced comics series Civil War—a title that of course immediately seems to me to refer to the American Civil War—was made into a successful movie, Captain America: Civil War. It’s about superheroes fighting each other—hence the “civil war” among them. But among long-form graphic novels or graphic narratives produced recently, I can’t think of many off the top of my head that explicitly and polemically advocate for war, in addition to the many that are simply about war.

I do think that the works I write about reveal the horrors of war, sometimes from a very personal and moving perspective, but they don’t set out to be didactic or polemical. I write about Joe Sacco’s work that it isn’t about advocating for human rights, although it’s all about human rights and human rights abuses. Rather, Joe Sacco’s work to me is about being haunted—haunted by the Other and what she or he endures in war. So yes, I think this work can’t help but raise doubt about war, even if that’s not what its main goal is.

Robin Lindley: For the most part, Disaster Drawn focuses on male artists. However, you’ve interviewed some of the most prominent female cartoonists such as Lynda Barry, Alison Bechdel, Marjane Satrapi, Phoebe Gloeckner, and others, for your wide-ranging book Graphic Women. How are women who create graphic nonfiction dealing with trauma and disaster?

Professor Hillary Chute: Alas, I haven’t interviewed Marjane Satrapi! She is an Iranian cartoonist who now lives in France, and I haven’t had the chance to talk to her directly, although I write about her book Persepolis in Graphic Women, and will write about her again. She is an artist whose work bridges the tradition of comics narratives about growing up in complicated, even traumatic family situations—of which many are by women—and the tradition of comics narratives exploring war and wartime, of which many are by men. (Of course, as a rule, this breakdown is over-general; there are plenty of exceptions.) Persepolis is about the author’s experience growing up in Tehran during the Iran-Iraq War and the ascendancy of the Islamic Revolution. Maus is also a book that bridges these very broad categories: it is about a family dynamic, and about World War Two.

In Graphic Women, most of the cartoonists I write about have experienced trauma in spaces that are generally conceived of as private: within the home, for instance, due to sexual abuse. Their trauma is often of the kind thought of as private and “personal,” as opposed to public, collective, and world-historical, like besieged civilians in a war zone. But what all of the comics works I have ever written about share, regardless of whether they are by women or men, is that they all show how the personal is political, and the political is personal, and categories of “private” and “public” blur. Across the board they reveal this, whether they are about growing up gay in rural Pennsylvania with a closeted father (Bechdel’s Fun Home), or whether they are about Palestinian families struggling on the West Bank to make ends meet as their homes are demolished in an ongoing conflict that has the world’s attention (Sacco’s Footnotes in Gaza).

Robin Lindley: You’re a professor and teach graphic nonfiction, among other courses. What interests your students most about cartoons and storytelling? How do they respond to portrayals of war and trauma? What does your work as a professor tell you about why graphic novels and related work are gaining in popularity?

Professor Hillary Chute: Students are interested in comics because it is a medium that is sophisticated, fascinating, and often very affectively compelling. The images in comics carry a charge: an urgency, an immediacy.

In a class I taught at Harvard last spring, a lecture course called “The Graphic Novel,” students had the option to create, for the final project, their own work of comics. I was blown away by how good these projects were, and from students with no previous comics experience. The combination of words and images is a compelling form for telling and showing real-life stories in particular—and trauma definitely was a part of this. I had students with many different national backgrounds in my class. My students’ own comics told and showed me about experiences around enforced abortions in China; about being at Harvard while being from another country where a family member had recently been murdered; about escaping a terrorist attack as a child; about surviving the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami.

People of all ages and abilities, it seems, can find a powerful voice in the combination of writing and drawing, words and images.

Robin Lindley: Thanks so much for your insights Professor Chute. Is there anything you’d like to add for readers on your book or plans for your future projects?

Professor Hillary Chute: I appreciate the opportunity to do this interview very much. My forthcoming book is called Why Comics: From Underground to Everywhere (HarperCollins). It relates to our interview today, in continuing my interest in comics and war and disaster. It has ten chapters devoted to the ten biggest (overlapping) themes in comics: Disaster, Superheroes, Sex, the Suburbs, Cities, Punk, Illness, Girls, War, and Queer. And the coda is on Fans.

Robin Lindley: Thank you again Professor Chute and congratulations on Disaster Drawn and your other pioneering works on the growing world of graphic novels and documentary storytelling. Your work also advances the history and understanding of visual reportage and trauma studies.

Oxford Comics Network, TORCH Networks