A History of Bookbinding as Told through Oxford College Libraries

A Research Micro-Internship with the Hidden Objects Project

The TORCH Heritage Partnerships Team, working closely with the University of Oxford Careers Service, set up this micro-internship with the Oxford-based project, Hidden Objects, which aims to enable the sharing of Oxford Colleges' collections with a wider audience.

In December 2021, I undertook a week-long Micro-Internship with Hidden Objects Oxford, a wonderful coalition of University-based and independent curators and researchers who are investigating the hidden gems of art in Oxford colleges. What followed was an exhilarating journey through many college libraries to uncover the history of bookbinding. With each college library home to thousands, often tens of thousands, of books and manuscripts, Oxford colleges are treasure troves of hidden objects which contribute greatly to the history of bookbinding.

Prior to modern books, the earliest form of writing is the cuneiform (wedge-shape) found on clay tablets in Mesopotamia, with assets recorded by pictures from 3200 BCE until the first century CE. Wooden tablets filled with wax were used until the Roman period.

The papyrus plant grows in Africa, Madagascar and the Mediterranean and its pulp was used extensively in Ancient Egypt and the Mediterranean, often in scrolls.

Papyrus, parchment (the stretched skin of a sheep) and vellum (the stretched skin of a cow) were used in scrolls and codices, precursors to the modern book. Magdalen has quite the claim to fame when it comes to the history of codices, holding some of the oldest known fragments of a codex. The Magdalen Papyrus P64 (Magd. MS. Gr. 17) are three double sided fragments of the New Testament probably dating to the late second century AD. We know that they are from a codex because they have text from the same chapter, Matthew 26, on both sides. In that chapter, Jesus’ head is anointed with perfume by a figure identified by some as Mary Magdalene. It is thought that 1901 donor Charles Bousfield Huleatt therefore donated them to the college named after her, although how he acquired them is unknown. Although none of the binding is intact, these oldest items in Magdalen’s collection by some 1000 years are an interesting early stop on the book history journey.

From papyrus to vellum and across many centuries, we encounter a Breviarum Bartholomew, a hefty summary of other medical texts from around 1410, housed at Pembroke College library. Featuring sturdy wood panels and studs to keep the cover raised from surfaces, these features and the good quality of vellum suggest it was valued more than its limp parchment counterpart with ineffective leather thongs as clasps. The latter, MS 2, exhibits another key quality of medieval and early modern books: it is home to multiple texts rebound together in one place. Cheaper and more convenient than separate costly bindings, this practice meant that the pages of different texts were often different sizes, lengths and types of vellum from each other.

The coexistence of various texts bound within one book did not stop with Pembroke’s on-the-job, portable, light medical compilation. Pastedowns, the reuse of older ‘scrap’ paper from dismembered manuscripts and books within or under books’ inside covers, was common to many early modern and modern books. Pembroke even hosts a book bound with a beautiful cover of early modern sheet music! In Magd. Arch. B.II. 4. 2 and 1, Biblia cum postillis Hugonis de Sancto Charo, 1498–1502, the binder’s waste provides us with what Magdalen think is the only evidence of the Long Parvula, a textbook forming part of the late medieval curriculum, attributed to John Stanbridge, Usher of Magdalen College School in 1486 and Master in 1487. Given the usual paper covers of such textbooks were flimsy and few have survived the hands of children, this pastedown embodies the multiple histories and texts encased within one bound book. Thought to be by the ‘dragon binder’, these volumes do not, however, feature the ‘dragon stamp’. Gibson (1903) thinks that only one (unspecified) volume of the set retains its original binding, demonstrating the large extent of rebinding, particularly among the wealthy.

A similar wonderful text within a text comes from Keble’s Millard 41, which features four seventh-century fragments used in the binding of a fifteenth-century printed copy on paper of Eusebius’ De evangelica preparatione (Venice, 1473). The fragments, which lined the spine panels between the sewing supports, are thought to be c. 785-821, and are part of a Gregorian sacramentary written for Arno, first bishop of Salzburg, contemporary of Alcuin of York, close advisor to Charlemagne, thought to have introduced the Carolingian Renaissance to Bavaria. This binding also features some more exciting aspects: small wooden wedges were used at the entry holes to trap and hold the cords before they were pegged finally at the exit holes. Despite being a Venetian binding, many aspects of it are typically German, including fore-edge clasps which clasp on the upper cover rather than the lower board. Reflecting the way repairs can change a book’s binding, in 1968 the spine covering leather was lifted to reattach the boards and the 8th/9th-century fragments were taken out, guarded onto paper and resewn at the beginning of the manuscript, where they are today.

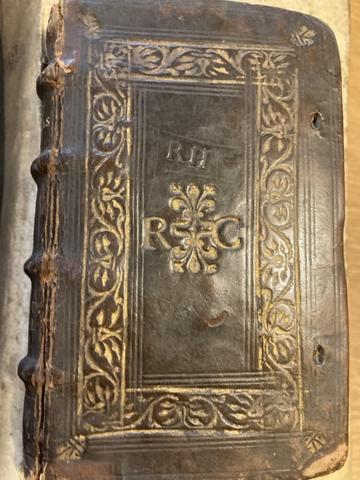

Another intriguing facet of bookbinding is its use to signify individual prestige and uniqueness. Whilst wealthier colleges could afford to uniformly rebind some books with college binding, some colleges were more reliant on individual donations, in whatever bound form they came. When Hertford called out for book donations in the seventeenth century, people responded generously. Many of their bindings were quite personalised, such as the proud red leather label with gold tooling, spelling ‘Martha Moor 1700’, on the calfskin leather of an edition of Whole duty of man necessary for all families and the stamps of initials “R.C.” and then ‘R.H” on the possibly 16th-century binding of Libri prophetarvm. Some sought to represent their book ownership through symbolic means, with Magdalen home to a number of armorial bindings including Magd. R.3.19, a fifteenth-century golden-brown leather calfskin-bound Psalmes of David in meetre, featuring gold-tooled double-fillet borders with floral and leafy stamps and the arms of Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales and son of James I. And sometimes the colleges have left ownership marks on their books, with a late twentieth century librarian at Lady Margaret Hall responsible for all of the rare books having marker pen catalogue numbers on their spines and many heavily covered in black tape as repairs!

Aside from owners of books, binders themselves have made their marks. Keble has a true treasure in this regard, a 1662 first edition Book of Common Prayer printed by John Bill and Christopher Barker, printers to the King. The contemporary binding features the ‘cottage roof’ style, with black goatskin onlays on the central panel in the shape of the top and bottom of a roof. Potentially bound by Royal Binder Samuel Mearne, the large red leather book features exquisite gold tooling. Magdalen boasts bindings by both the 15th-century ‘greyhound binder’ (MS. Lat. 58) and the 15/16th-century ‘Dragon Binder’, both known for their distinctive stamps imprinted into leather. An architect of both the interior and the exterior of books, William Morris was inspired by the 16th-century, and it is interesting to compare his works with 16th-century books housed in the same rare books collections in college libraries. Lady Margaret Hall library holds a late 16th-century publication of Julius Caesar’s Commentaries on the Gallic War bound in limp parchment with book ties which may be described as yapp fore-edges, book ties named after 19th century London bookseller William Yapp. LMH also holds a late 19th-century William Morris limp parchment binding with yapp fore-edges which looks remarkably similar.

On the topic of flaps and clasps, many solutions have been employed to keep books tight and maintain the flatness of pages. The Queen’s College’s MS. 316, Deutoronomy, with the Glossa ordinaria, features a medieval, possibly original, English binding. The large book is bound with plain, dirty leather and has an impressive strap-and-pin fastening at the fore-edge. There would have originally been two.

Flaps have also been used to protect books, seen on MS. 309 at New College, a 15th-century Qur’an featuring a fore-edge flap and recessed decorative panels. A few hundred years later, a flap was also used on a 17th-century Qur’an held at Lady Margaret Hall. The fore-edge flap was a typical element of Islamic binding, providing protection to the book when closed. Because the depth of the flap is smaller than that required by the book, it is thought that the binding has been repurposed from another book of a similar size. Reflecting the dedication of repairers, the new spine is a similar red and may be missed at first glance. Indeed, even college librarians can’t always detect whether books have been re-backed, repaired or rebound centuries after their first binding, reflecting the impressive art of repair.

By the end of the week, I was fluent in bookbinding terms previously alien to me, could competently handle rare books, and had only scratched the surface of a brilliant iceberg of many thousands of beautiful books lovingly preserved but tucked away in college libraries. These books, through their physical construction, reconstruction, wear and repair, lives and afterlives, shine a magnificent light on so many aspects of history. They truly are hidden objects which deserve to be (carefully) uncovered.

Bibliography

‘What is a book?’, the Society of Bookbinders https://www.societyofbookbinders.com/what-is-a-book/

‘The Magdalen Papyrus P64: possibly the earliest known fragments of the New Testament (or of a book!)’, Illuminating Magdalen, Magdalen College website (2013)

https://libguides.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/lmh/bookbindings

‘Bookbindings at Keble College – a book conservator’s vade mecum’, Jane Eagan for Keble College website https://heritage.keble.ox.ac.uk/special-collections/bookbindings-at-keble-college-a-book-conservators-vade-mecum/

‘Judging a book by its cover: bindings in Magdalen College library’, exhibition catalogue curated by Anne Chesher at Magdalen college (2015)

‘Lady Margaret Hall Library: Bookbindings’, online exhibition on Bodleian website (last updated 2021) https://libguides.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/lmh/bookbindings

Hope Philpott is a second year History student at Pembroke College. She works on early modern and modern history, with particular interests in gender, religion, colonial experiences and investigating history through a variety of media, including art.

To learn more about our collaboration with the Hidden Objects Project and more micro-internships hosted by them see:

John Piper: Artist In Stained Glass

Weaving tales of the Green Man: A journey into John Piper’s hidden tapestries

Oxford’s Mortlake 'Supper at Emmaus': A Look into St John’s President’s Lodgings

Hertford College Library VVV.1.1, Libri Prophetarum. A probable 16th century binding of calf over boards, featuring central stamped initials "R.C." with ornament and the initials "R.H." stamped above this at a later date, suggesting two sets of personal ownership of the book